Cognitive and psycholinguistic relations of the Cypriot Greek speaker with language(s)

Résumé

Le présent travail examine les relations psycholinguistiques et cognitives – en termes de néoténie linguistique- que le locuteur chypriote grec maintient avec cinq codes linguistiques : le chypriote grec, le grec moderne standard, l’anglais, le français et le turc. Une méthode analytique est utilisée afin de découvrir ces relations cognitives. La théorie de la néoténie linguistique est utilisée comme un outil, car nous considérons cette théorie comme la plus adéquate d’offrir des informations spécifiques. Les relations cognitives et psycholinguistiques que maintient un locuteur avec des langues, peuvent être examinées uniquement en adoptant une perspective synchronique puisqu’elles peuvent se modifier au cours du temps. Pour cette raison, dans ledit travail nous n’examinons que le cas des locuteurs chypriotes grecs âgés de 34 à 45 ans.

Mots-clés : linguistique cognitive, locuteur chypriote grec, langue in esse, langue in posse, langue in fieri, néoténie linguistique, psycholinguistique.

Abstract

This paper examines the psycholinguistic and cognitive relations -in terms of linguistic neoteny- the Greek Cypriot speaker maintains with five linguistic codes; Greek Cypriot, Standard Modern Greek, English, French and Turkish. Using synchronic data and adopting an analytical method (quantitative, qualitative approach) as well as a dialectical method, this paper aims to discover the cognitive relations the Greek Cypriot speaker maintains using the above five linguistic codes. To do this, we use the theory of linguistic neoteny as we believe that it is one of the most adequate theories which can provide specific information concerning these cognitive relations a potential speaker maintains with their spoken language(s), either it’s chronologically their first, second or third. As these relations are subject to be modified in the course of time, applying a synchronic perspective is the only way a theoretical linguist can examine them. Therefore, in this paper we are examining only the case of the Greek Cypriot speaker aged between 34 and 45 years old.

Keywords: Cognitive linguistics; Greek Cypriot speaker; in esse language; in fieri language; in posse language; linguistic neoteny; psycholinguistics.

1. INTRODUCTION

Much of the language processing happens subconsciously and psycholinguistic theories are being used to study in depth these language-processing mechanisms. This is highly related to cognition and cognitive development as language(s) acquisition is formulated by these mechanisms and has an impact on them (O’Grady, Dobrovolsky, & Katamba, 1997). Speaking a language is far more complicated than just placing words and sentences in a row. It is about seeing the world through that language and expressing oneself according to what that language permits (Bajrić, 2009). In the case of bilinguals and multilinguals, things are far more complicated but this is the case of speakers who are most commonly found today. It is so necessary nowadays to be able to express oneself in different languages that it is out of the question to stay monolingual even in the smallest village (Rezapour, 2016, p. 30)

Before addressing the subject of relations between speakers and languages, it is crucial to initially define, what speaking a language means. Speaking a language is having (at least) some level of linguistic knowledge, i.e. be aware of the syntactic, grammatical and morphological rules of that language and speak according to these rules in order to achieve communication. However, this definition seems inadequate. According to Bajrić (2009) our whole identity is defined by the language we speak. It is easy to understand the grammatical function of one language and it is the part the most easily accessible, by using traditional language learning (a class, a teacher and a student). However, the real heuristic dimension is not found in books. This dimension is about being able to reach a psycholinguistic level where intuition leads the speaker to choose one phrase over another. It is about knowing the language’s boundaries and learn to express respecting them, based on the unique communicative circumstances the speakers come across each time they speak. Bajrić (2009, p. 110) then goes on to talk about language permissiveness (vouloir-dire) and refers to the language’s boundaries a speaker must respect, otherwise they risk falling in some major misunderstandings. While the phrase break a leg is perfectly acceptable by the English language to imply good luck, it is by no means acceptable neither by the Greek nor the French language. When we speak another language, we don’t only achieve some communicative purposes. It is about rediscovering a different world, it is about knowing -in a cognitive way- things in another language and, since everything a language consists of modifies our cognitive functions, it therefore modifies our way of being. In this point of view, speaking a language means being, existing in that language (Bajrić, 2009)

Before examining the complex case of a multilingual speaker, it is of vital importance to refer to the psycholinguistic state of a bilingual speaker. Rezapour (2016, pp. 34–38) argues that even though there are many studies about bilingualism providing definitions and descriptions of bilingualism like the work of Olivier Soutet (2005), Bloomfield (1935), Macnhamara (1967), Titone (1974), Weinreich (1979), Haugen (1953), Hagège (2005), they, nevertheless, provide one-dimensioned definitions of bilingualism, that is the competence of the bilingual speaker in two languages. Rezapour is highly interested in the cognitive organisation of the bilingual system and since bilingualism is the simplest form of multilingualism (Rezapour, 2016, p. 32), we use the same theory in this paper to examine the interesting case of the multilingual Greek Cypriot speaker.

Two questions immediately emerge. Firstly, why this particular speaker? This particular speaker drew our attention because of the number of languages they come across throughout their lives, starting chronologically from birth to adulthood. To make it clearer, chronologically, this speaker has come across at least five linguistic codes throughout his/her life. Up to the age of six this speaker speaks Cypriot at home with family members and friends. At the age of six, when he/she first enters primary school and comes in contact with the Greek language- one of the two official languages of the Republic according to the Institution established in 1960. Mostly because Cyprus has been a British colonisation for many years (1878-1960) but also due to the massive number of tourists, along with many foreign companies, learning English is a necessity for these speakers. The French language first appears at elementary school, since it is part of the curriculum and students are mandatorily being taught French for four years, three at elementary school and another one in high school, having the right to choose this language as an elective for the final two years of schooling. Last but not least, the Turkish language which the other official language of the Republic, along with Greek, it is found written on every official document issued by the government like identity cards and passports (Tsiplakou, Hadjioannou, & Kappler, 2011).

The aim of this paper is to discover the cognitive relationships the Cypriot Greek speaker maintains with these five languages. To be more specific, in this paper we aim to discover the cognitive relations that the Greek Cypriot speaker maintains with the linguistic codes found on his/her linguistic environment; those languages being the Cypriot, the Greek, the English, the French and the Turkish. To do so, we use the tools provided by the very recent theory of linguistic neoteny inspired by Samir Bajrić (Bajrić, 2009). As we have mentioned at the beginning of this paper, the relationship between a speaker and a language can only be examined synchronically and never diachronically since they are subject to be modified, or radically changed through time. To give an example, the cognitive relations between a twelve-year-old Greek Cypriot speaker with French is different than twenty years later when he is twenty-two years old. At twelve he is taught French at school but at the age of twenty-two his linguistic reality has probably nothing to do with the French language. The same goes for a seventy-year-old man who had another relation with the Turkish language before the island’s invasion in 1974 and today. Before the partition, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots were peacefully and harmoniously living together and our research shows that many speakers knew at least some Turkish. In light of evidence that the Turkish language was not an unknown language for them, or in terms of linguistic neoteny, it was not an in posse language for them. Today, forty-four years later, the exact same speaker, remembers nothing of this language. It is therefore clear, that age and time play a significant role when it comes to identifying the relationships between speakers and languages. The interesting case of this multilingual speaker is examined by using the means provided by the theory of linguistic neoteny. At this point, the second question emerges: Why this particular theory?

2. THE THEORY OF LINGUISTIC NEOTENY

“There resides in every language a characteristic world-view […] to learn a foreign language should therefore be to acquire a new standpoint in the world-view hitherto possessed” wrote Wilhelm von Humboldt (1999, p. 60). The theory of linguistic neoteny and W. von Humboldt share the same ideas when it comes to speaking one language and learning another. The theory of linguistic neoteny is a relatively recent one and it is described to be the theory of the unconfirmed speaker, the uncompleted being. The word neoteny is borrowed by the biologist Louis Bolk who used it to describe the delaying or slowing of the normal, physiological development of an organism. As a starting thought, the French linguist Samir Bajrić published a book in 2009 named “Linguistique, cognition et didactique” where he analyses, for the first time, this new theory offering to the world of theoretical linguistics a different point of view of the cognitive relations a speaker maintains with language(s). This theory describes the state of the speaker who is no more monolingual and acquires another language when he/she is linguistically an adult – that is above the age of 10-11. This speaker is considered to be an uncompleted being, because of their uncompleted language mastering.

A speaker may be excellent in using the language according to the grammatical, morphological and syntactical structures of that language but not be able to understand everything that is going on a dinner table with native speakers of that language. Teachers and instructors get to hear many times a phrase like “I know the words, but I don’t get the meaning” Why?

The answer to the above question is because, besides the linguistic structures (assimilation linguistique) the speaker also needs to acquire the more complex structures and the different meanings of words and phrases (assimilation comportementale), something that is not found in books. A phrase like “Ça y est! Les résultats sont tombés!” would cause a lot of problems to a Greek-Cypriot speaker trying to acquire the French language. Even if this speaker knows every word of this phrase, he or she will not be able to understand the meaning of it and word by word translation cannot help in any case.

What is more, each language follows a certain way to describe the world. There are some boundaries set by the language itself that the speaker needs to respect. It’s what the language permits to its speakers and it’s what Bajrić refers to as the “vouloir-dire de la langue”. In linguistic neoteny therefore, this includes all the elements that the language permits its speakers to articulate, like the example of wishing good luck we have referred to, earlier. Part of the language’s vouloir-dire is also silence. Not speaking a language means that we do not exist in that language, that we haven’t got any sort of linguistic or mental identity in that language. However, knowing when to choose silence over speaking, means the speaker possesses a linguistic and most probably a mental identity in that language; as knowing when to remain silent is not part of any linguistic assimilation, but is more like having a linguistic behaviour which is usually gained by language immersion. Mastering a language is not only about linguistically making the correct choices but also knowing when and where to remain silent.

Cognitively speaking, language, resides in us and we live in that language. Samir Bajrić states that when we speak a language, our psychology and cognitive features are registered in that language. When we learn another language, we do not replace words with other words. We learn the new words the second language offers and we create a new system of cognitive organization. It is about knowing -in a cognitive way- things in the other language because when we speak another language, we do not say the same things.

When we speak a language, we validate our existence and therefore speaking it means being, existing. Language learning that comes later in a speaker’s life forces him to find a way to exist in the second language; to find a new linguistic and psycholinguistic identity. Additionally, any language learning that comes later in a speaker’s life usually occurs in an institutional framework and, despite some improvised situations; it is in its majority artificial, decontextualized and not authentic (Bajrić, 2009). Therefore, gaps are being created between the speaker who speaks that language since birth and the speaker who acquires that language later in life. Only language immersion can fill these gaps and if this doesn’t occur, then the speaker will probably not be able to find a new linguistic and mental identity, thus will not be able to exist in that language.

These linguistic or even psycholinguistic incompleteness since neither their utterances nor their linguistic behaviour is fully developed like they are in the case of a native speaker, is what the theory of linguistic neoteny advocates. It’s the theory of the “uncompleted being” (“être inachevé” (Bajrić, 2009, p. 41)) and in terms of linguistic neoteny, speakers are divided into two major categories: the confirmed speakers and the non-confirmed speakers.

The confirmed speakers (locuteurs confirmés) are the speakers who have the ability to express themselves spontaneously and without any hesitation since a very young age. They, therefore, have managed to find their linguistic and ontological identity in a language. They have a high level of linguistic intuition, they know the language’s boundaries, respect them and express themselves according to what the language permits (d’après la génie de la langue). On the other hand, the non-confirmed speakers (locuteurs non-confirmés) are those who haven’t been able (yet) to create this mental agreement between the new linguistic code and their existent mental code, between who they are in their first language and who they could become in the new language.

This is a linguistic research and more specifically a theoretical linguistics research. Therefore, we find that some terms borrowed by the educational field are neither adequate nor prove to be sufficient to the content we want to assign to them. For example, if we talk about mother tongue, it is generally accepted that we talk about the mother’s language, the first language a child speaks at home. However, in many cases like the orphans or refugees this is definitely not true. What happens in the case of a seventy-year-old man who immigrated with his family at the age of five in another country? He spent almost all his life speaking a new language that is not the language of his parents. How do we define his mother tongue? Moreover, as we mentioned earlier in this paragraph, this theory aims to discover the psycholinguistic/cognitive relations between speakers and languages and the term mother tongue does not provide any information of this kind.

Bajrić describes the psycholinguistic relations speakers hold with languages they speak by introducing three new terms: the in esse language, the in fieri language and the in posse language(2009, p. 31,35).

In esse language: every natural language (not constructed, not artificial) where the speaker has acquired a grammatical and linguistic intuition (confirmed speaker)

In fieri language: every language which the speaker can use to communicate in different contexts but they do not have a developed trustworthy linguistic intuition. (unconfirmed speaker)

In posse language: every language in which the speaker doesn’t recognize any features or barely recognizes some of them. (Unconfirmed speaker)

These terms are not here to substitute the traditional terms used by teachers, professors or even other linguists. On the contrary, they are here to complete the traditional terms, in the sense that they provide a different way of viewing, understanding and analysing the relations between a speaker and a language, as they provide some evidence of what is happening cognitively and psycholinguistically within the speaker.

If we consider the fact that we cannot speak two languages at the exact same time, then that means that we cannot think at two languages at the exact same time. Following the same way of thinking, we cannot exist in two languages at the same time as our cognitive features cannot be inscribed in two languages simultaneously. The presence of a second language forces the speaker to overcome their natural specialisation that is the monolingualism. Learning a new language and inserting another linguistic behaviour means that another mode of “being” is required too. The self-sufficiency acquired by the monolingual status ceases to exist.

According to Rouhollah Rezapour who uses the theory of linguistic neoteny to describe the cognitive relation in Persian - French bilingualism, argues that this theory brings forward an approach to the cognition in the language appropriation; linguistically and psycholinguistically the speaker is considered to be an uncompleted being but who is though in a constant stage of improvement (2016, p. 77). This speaker is already a confirmed speaker in one language and seeks completeness in a second one. However, in the second language there are many difficulties to face in order to be able to express oneself spontaneously.

The case of the Greek Cypriot speaker is being analysed here because it is a speaker who -chronologically - has been through many linguistic turbulences but also synchronically many languages co-exist in their immediate linguistic environment. The purpose of this paper is to uncover the cognitive relations (in linguistic neoteny terms) this particular speaker maintains with language(s) and observe whether this speaker succeeded in relating his linguistic and ontological identity in any of the five linguistic codes found around him; Cypriot, Greek, English, French, Turkish.

Our purpose is to discover the cognitive relations that the Greek Cypriot speaker with the five linguistic codes mentioned above has. We are aiming in finding out the linguistic code(s) this speaker has managed to find their linguistic and mental identity. We can only examine the cognitive relation synchronically, therefore we are presenting the findings of one age group. This is a part of a bigger research containing participants from all age groups. However, in this paper we are presenting the findings of 81 Cypriot Greek speakers aged between 35-44.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Participants

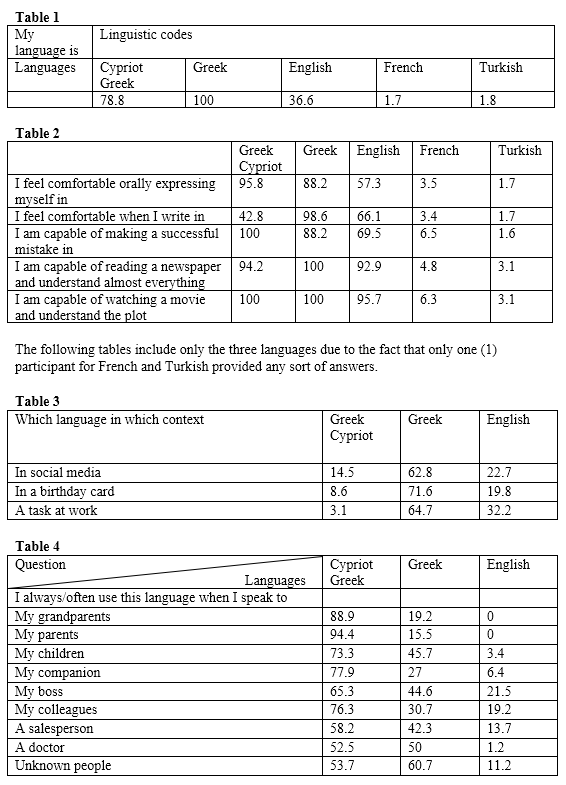

A number of questionnaires were sent to speakers, 176 were returned completed and the results were converted in tables. We divided the participants into age groups and in this article, we examine only speakers aged between 34-45 years old (81 participants: 37 men, 44 women). The educational level of the participants varied between high school and post-doctorate.

3.2. Data collection

This research took place between March 13th and March 25th 2018. It is important at this point to state that this is an ongoing research. Data collection was possible through questionnaires. The questionnaire was designed in the Standard Modern Greek language and the purpose was to collect linguistic and psycholinguistic information. The questionnaire was divided into five parts including multiple choice questions on Linkert scale as well as open-ended questions. The first part was the introduction indicating the number of the questions included in the questionnaire, informing the participants that it is part of a PhD thesis research and that it is conducted anonymously. Moreover, it clearly stated that the specific questionnaire is only to be completed by speakers who were born and raised in Cyprus or who have moved there soon after their birth. The second part was about eliciting demographic data as well some personal information like education, age and occupation. The third part focused on general linguistic information and the fourth part aimed at some linguistics-related questions. The final part targeted at examining the psycholinguistic relations of these speakers with the five linguistic codes. The questionnaire was made by using the Online platform “Survey Monkey” and was sent to participants by using the internet and more specifically by using the email and various applications like messenger, WhatsApp and Viber

3.3. Interviews

Along with the questionnaires, personal interviews are being conducted aiming to back up the results that emerged from the questionnaires. Most of the interviews were free of set up and pre-arranged questions. They, in all cases, had the form of a discussion around the subject of the use of these five linguistic codes.

3.4. Results

Below are some of the answers we received. The results are in the form of percentage (%)

4. Discussion

Before discussing the findings of this research it is important to state that out of the interviews conducted after the collect of the questionnaires it was evident that many Greek Cypriots believe that they are speaking in Greek and writing in social media using the Greek language but what they are actually doing is using the Cypriot language is its more acrolectal terms something that is in line with the findings of other linguists (Arvaniti, 2006; Ioannidou, 2009, 2012; Tsiplakou, 2006). However, even in its more acrolectal pole, the code that these speakers use is not identical to the one spoken in Greece.

The first linguistic code to be analysed here is the Cypriot Greek. This code has raised a series of debates between the Greek Cypriots and most of them had a political background. One political party, the left party, wanted Cyprus to be an independent state and on the other hand the right party was seeking the Enosis, that is the union with Greece, supporting that Cypriots and Greeks share the same blood, the same language and the same culture (Karoulla-Vrikki, 2007, p. 83). Therefore, a part of the population believed that the language of the Greek Cypriots is the Cypriot dialect, while others claimed that Cypriots should speak Greek.

The truth however is found in the middle. Tsiplakou (Tsiplakou, Papapavlou, Katsoyannou, & Pavlou, 2007, p. 10) mentions the terms basilect, mesolect and acrolect referring to the language continuum of the Cypriot Greek. Moving from the ‘heavy’ spoken Greek Cypriot to the Cypriot standard Greek, somewhere in between lies the ‘tidied-up’ Greek Cypriot and the ‘polite’ Greek Cypriot. Karyolémou (2000) showed that it is not actually about choosing between the two codes but more about expressing either by using more basilectal features or more acrolectal ones with the result being most of the time somewhere in the middle. In this study our participants defined the Cypriot as a linguistic code found somewhere in the middle between the ‘heavy’ spoken Greek Cypriot – not frequently met among younger speakers- and the Standard modern Greek; fact that is in line with the Cypriot standard Greek of Arvaniti (Arvaniti, 2010).

As it is mentioned above, many studies (Papapavlou, 1998, 2001; Papapavlou & Sophocleous, 2009) have proven that for many years the linguistic code spoken in Cyprus was attached to negative notions and was stigmatised and associated with naturally occurring talk and informality (Ioannidou, 2012, p. 263). Our research showed that despite this stigmatization, 80% of participants of this age group consider this linguistic code to be their language, feeling comfortable in speaking in this language and all of them defended the opinion that they can definitely make a joke in the Cypriot Greek and watch a movie or a series and understand almost everything. Psycholinguistically speaking, these answers show us that the Greek Cypriot speaker has managed to unify their linguistic and metal identity in this linguistic code. Their preference in this linguistic code shows the level at which they are comfortable in using it. In terms of linguistic neoteny we are certain that this code is an in esse language for these speakers at the present time. It seems that they have managed to find their linguistic and mental identity which are unified. They possess a high level of linguistic intuition and they are able, not only to communicate by using this code, but also to make a joke and to keep up with a pure monolingual Cypriot native speaker – irrelevantly if such speakers are more and more rare to be found these days. On a potential dinner between Greek Cypriot, speakers this age group wouldn’t have any problem in understanding everything linguistically. Moreover, they would be able to behave according to what this linguistic code permits, they already know its boundaries and respect them. Therefore, not only this speaker has reached a high level of linguistic intuition, but also possesses a proper and adequate linguistic behaviour. In terms of linguistic neoteny, the majority of this age group is a confirmed speaker of the Cypriot language which makes this code an in esse language for them.

The second linguistic code is the Greek language, one of the two official languages stated in the Cypriot Institution established in 1960. It is the language of the media and the official language of the school system, even though ‘the claims made by policy-makers that the language of the classroom is Standard Modern Greek are not valid […] the Greek Cypriot is widely used both by the students and the teachers on various occasions in the classroom’ (Ioannidou, 2009, p. 275). Our research showed that a big majority of these speakers use the Greek language when talking to their boss, a doctor or unknown people, something that Ioannidou also suggested that The choice of linguistic variety depends on the occasions of communication, having the Standard associated with formality and appropriateness […] while the Cypriot Greek is mostly associated with naturally occurring talk and informality (2009, p. 263).

What is worth noting here is that, this big majority also uses this code to talk to their children, which is accepted to be one of the dialogues dressed with intimacy and affection. We would normally expect to find the Cypriot Greek used in these cases. This may be an indicator of the Greek language gaining ground among the younger generation and gradually penetrating and influencing the way the Greek Cypriots speak. By further analysis of our results, we observe that all of them consider the Greek language to be their language implying a direct connection with their mental identity. However, there is still this 10% who doesn’t feel comfortable talking in Greek, and neither they feel that they can they make a successful joke in this language. As there are no clear boundaries between the cognitive relations speakers maintain with languages, we cannot define with exactitude this relationship.

If we define the Greek language as the one spoken in Greece, then talk about an in fieri language for the majority of these speakers as the code they use is not identical to the one the Greek speakers use. If we define Greek language as the acrolectal part of le language continuum then we would day that it is an in esse language. The Greek language as it is spoken in Greece is definitely an in fieri language for many Greek Cypriot speakers of this age. They are, therefore, not confirmed speakers of this language.

English language is crucial in the lives of these speakers. They spend all their school years learning English, many of them have a job where English is a necessary qualification, watch movies and TV series in English, while almost all of them can read and understand an English newspaper. With this language being actively present in their everyday lives, half of these speakers even consider it to be their language and more than half stated that they feel comfortable speaking in it. It is perfectly clear that the majority of this age group is really competent in English but this does not account as a witness that they have found a way to exist in this language. Based on our results, the majority of this age group has not been able to unify their mental and linguistic identity. Cognitively speaking, they don’t seem to have an accurate mental representation of English and we can fairly say that it is not an in esse language for them. It is though, an in fieri language they can communicate efficiently but do not possess an advanced level of linguistic intuition.

Concerning the French and the Turkish language, the greatest majority of this age group has nothing to do with these two languages. Even though they were taught French for four years during schooling, and coming across the Turkish language occasionally on TV programs but also in the written form on every governmental paper they have, both of these languages are in posse languages for them. That means that cognitively they do not have any mental representations in these two languages except maybe one or two words. During their schooling time, the French language would probably an in fieri language. In contrast, as the cognitive relations we maintain with languages are highly connected to age, time and circumstances, this one has also been modified through time. These two languages are clear examples of languages in posse for the specific speakers. They have certainly not found any sort of linguistic identity in these two languages despite their presence in their lives. The large majority of the Greek Cypriot speakers of the age of 34-45 are non-confirmed speakers of the French and Turkish language.

5. Conclusion

In this research, we have tried to bring to the surface the psycholinguistic relations the Greek Cypriot speaker of the age of 34-45 maintains with five linguistic codes. To do this, we used the theory of linguistic neoteny as it is a theory providing the way to define these relations. Our research came to the conclusion that the Greek Cypriot speaker of this age group has one in esse language which is the Cypriot Greek. They found a way to exist in this language and they possess a high level of linguistic intuition. The Greek language is a language dressed with some characteristics of an in esse language, but we cannot argue in any case that the majority of this age group has managed to find their way of being in this language.

Despite the high level of linguistic competence in English, our research showed that this is an in fieri language for these speakers as their cognition is yet to be altered and modified by English. They are unconfirmed speakers of the English language. As regards the French and the Turkish language, despite their presence in these speakers’ lives, there is no trace of having any linguistic or mental relation, leading them to be two in posse languages.

It is true though, that more work is subject to be done, as more evidence is needed, to help us discover the cognitive organisation of this specific multilingual speaker. More research is required to reinforce the results of the research already conducted. It is crucial to examine more thoroughly the relations between of the two major linguistic codes found on the island –Cypriot Greek and Standard Modern Greek –, determine their boundaries, before providing more analytical results about the cognitive relations the Greek Cypriot speaker maintains with them.

Moreover, the analysis of the similarities and the differences between different age groups is what will shed more light. The cognitive relations of a speaker, as we’ve shown earlier, in his early twenties are completely different from the one in his sixties. Therefore, comparing different age groups is also crucial to extract more specific and analytical results concerning the cognitive relations between Greek Cypriot speakers and these five languages mentioned in this paper, with the Cypriot Greek, the Standard Modern Greek and the English language having a more outstanding place.

References

Arvaniti, A. (2006). Erasure as a means of maintaining diglossia in Cyprus. San Diego Linguistic Papers, (2), 25–38.

Arvaniti, A. (2010). Linguistic practices in Cyprus and the emergence of cypriot Standard. Mediterranean Language Review, (2), 15–46.

Bajrić, S. (2009). Linguistique, cognition et didactique. Principes et exercices de linguistique-didactique. Paris. Presses de l’université Paris-Sorbonne.

Bloomfield, L. (1935). Language. London: Allen and Unwin Ltd.

Hagège, C. (2005). L’enfant aux deux langues. Paris: Odile Jacob.

Haugen, E. I.(1953). The Norwegian Language In America: a Study In Bilingual Behavior. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Humboldt, W. von. (1999). On Language: On the Diversity of Human Language Construction and Its Influence on the Mental Development of the Human Species. (M. Losonsky, Ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/3737478

Ioannidou, E. (2009). Using the “improper” language in the classroom: The conflict between language use and legitimate varieties in education. Evidence from a Greek Cypriot classroom. Language and Education, 23(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780802691744

Ioannidou, E. (2012). Language policy in Greek Cypriot education: Tensions between national and pedagogical values. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 25(3), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2012.699967

Karoulla-Vrikki, D. (2007). Education, Language Policy and Identity in Cyprus: A Diachronic Perspective(1960 - 1997. Sociolinguistic and Pedagogical Dimensions of Dialects in Education, (November).

Karyolémou, M. (2000). La variéte chypriote : dialecte ou idiome ? Α.-Φ. Χριστίδης et Al. (Επιμ.), Η Ελληνική Γλώσσα Και Οι Διάλεκτοί Της, Αθήνα: ΥΠΕΠΘ & Κέντρο Ελληνικής Γλώσσας, 111–115.

Macnamara, J. (1967). The linguistic independence of bilinguals. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6(5), 729–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(67)80078-1

O’Grady, W., Dobrovolsky, M., & Katamba, F. (1997). Contemorary Linguistics: An Introduction (3rd ed.). Longman. https://doi.org/10.2307/417683

Papapavlou, A. (1998). Attitudes toward the Greek Cypriot dialect: sociolinguistic implications. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 134, 15–28.

Papapavlou, A. (2001). Mind your speech: Language attitudes in Cyprus. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 22(6), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630108666447

Papapavlou, A., & Sophocleous, A. (2009). Relational social deixis and the linguistic construction of identity. International Journal of Multilingualism, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710802531151

Rezapour, R. (2016). Le bilinguisme en néoténie linguistique. L’Harmattan.

Soutet, O. (2005). Linguistique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Titone, R. (1974). Le bilinguisme précoce. Bruxelles: C. Dessart.

Tsiplakou, S. (2006). Cyprus: Language Situation. Elsevier, 337–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/01790-9

Tsiplakou, S., Hadjioannou, X., & Kappler, M. (2011). Language policy and language planning in Cyprus. Language Policy and Language Planning in Cyprus. Current Issues in Language Planning, 12(4), 503–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2011.629113

Tsiplakou, S., Papapavlou, A., Katsoyannou, M., & Pavlou, P. (2007). Pratiques langagieres et description lingustique en contexte bi-dialectal: le grec chypriote. In XXIXème Colloque International de Linguistique Fonctionnelle (pp. 109–113).

Weinreich, U. (1979). Languages in contact : findings and problems. The Hague:Mouton, 9.