Content and Language Integrated Learning for the Hospitality Industry

Ana GIMENO-SANZ, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain

Abstract

This paper starts with a brief introduction about Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and then goes on to describe the CLIL Open Online Learning (COOL) project and the development of Clilstore, a dedicated CLIL tool consisting of a multilingual dictionary interface, a system that automatically links all the words in a webpage to a selection of free dictionaries, and an authoring tool to create materials that combine content and language, as well as a repository of existing materials in over one hundred languages. The paper concludes with some teaching resources for the hospitality industry.

1 INTRODUCTION

CLIL, the acronym for Content and Language Integrated Learning, was launched in 1996 by UNICOM, University of Jyväskylä (Finland), and the European Platform for Dutch Education, and was recognized as a teaching methodology by the European Commission in its Communication No. 449 on Promoting Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity: An Action Plan 2004 – 2006, published in 2003. Throughout these years, we have witnessed how CLIL has steadily established its teaching principles and is slowly becoming a dominant methodology in all sectors of education that are sensitive to bilingual education. Research and reflective practice literature are currently abundant and CLIL has become the focus of an increasing number of empirical studies proving the methodology’s worth (Gimeno, Dónaill & Andersen, 2014).

As Marsh, Marsland & Stenberg (2001) put it “CLIL is an educational approach in which non-language subjects are taught through a foreign, second or other additional language”. As described by Darn (2006, p. 2), “the theory behind CLIL has foundations in interdisciplinary/cross-curricular teaching, which provides a meaningful way in which students can use knowledge learned in one context as a knowledge base in other contexts.” Non-linguistic content is used to teach a foreign language and students acquire new knowledge through the medium of that language. No doubt, however, students must have some basic knowledge of the language they are learning (Gimeno, 2021), e.g. A2 according to the CEFRL, in order to understand the content at an acceptable pace, within a particular context, and a basic understanding of the topic in their native language. Because the aim of a CLIL class is primarily the subject matter and the foreign language is secondary, despite it being a crucial pillar, students perceive the completion of language learning activities in a different light because the activities relate to the subject matter at hand and are therefore not devoid of context and meaningfulness. They gain meaning through being useful for a particular goal, that of understanding, exploring, and acquiring new knowledge relating to the subject matter. One could argue, however, that there is a narrow line between insufficient knowledge of the foreign language (FL), a fact that could lead to a breakdown in learning content, and having sufficient knowledge of the FL to delve into the content whilst simultaneously practising and improving proficiency in the FL.

There is little evidence, however, to show that the comprehension of content is impeded by lack of productive (versus passive) language competence (Gimeno, 2021); a student could very well engage in extensive reading and understand the meaning of the text and yet have a poor knowledge of the foreign language. If we take a technical text as an example, vocabulary is no doubt a key element so, if a student is capable of understanding the technical vocabulary in the text, s/he should be able to comprehend the general meaning of that text. Bearing this premise in mind, a consortium of European universities set about to create a tool that could help learners in their quest to learn content through the medium of a foreign language and facilitate this dual intake by providing elements to aid in scaffolding both content and language learning. The said tool, known as Clilstore, is described in the following section.

2 CLILSTORE

Clilstore was designed bearing in mind a number of generally agreed principles underlying CLIL (Darn, 2006: 2), which can be summarised as follows and which are constant reminders that learning takes place through language:

- Language is used to learn and communicate (receptive and productive skills).

- A CLIL lesson should combine content, communication, cognition (develop thinking skills), competences, and community.

- Language is functional and it is adapted to the subject.

- Language is approached lexically; grammar is not the most important element.

- Learner styles are taken into account in task types.

Thus, the concept of CLIL is in many respects similar to ELT for specific purposes, integrating all four skills; however, the former does not necessarily include explanations relating to the language itself, but simply involves understanding and production of the second language. A CLIL lesson framework could, for instance, be based on reading or listening comprehension texts and activities associated to the organisation of knowledge and textual processing. The subject specialist should not explain language structures or correct language inaccuracies as it is not his or her task; communication in this context is far more important than fluency or accuracy. Both content and language teachers should combine activities that are appropriate for that particular discipline with language learning exercises in order to balance knowledge intake. The subject specialist should be able to exploit opportunities to develop language skills as well as improving the acquisition of content, and vice versa (Carrió Pastor & Gimeno Sanz, 2007).

Although subject and language specialists have to work very closely in designing materials that are appropriate for the CLIL classroom and, subsequently, invest a large amount of time in doing so, we firmly believe that the advantages outweigh the burdens. Very briefly, these advantages can be summarised in the following ideas (Darn, 2006, p. 3):

- CLIL introduces a wider cultural context.

- CLIL prepares students for international activities and exchanges.

- CLIL gives access to international certification.

- CLIL improves general and specific language competence.

- CLIL prepares for professional life and provides more job opportunities.

- CLIL develops multilingual interests and attitudes.

- CLIL increases student motivation to learn a second or even a third language.

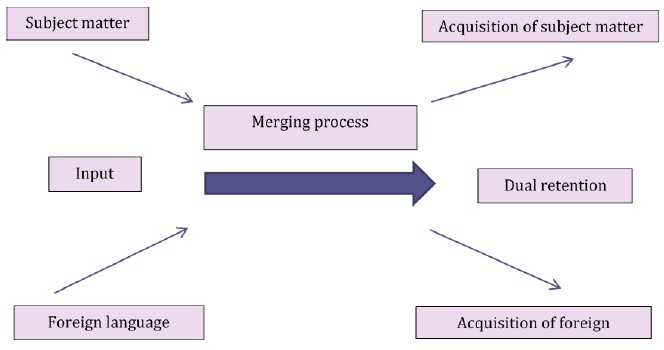

Several studies claim that CLIL is a source of motivation for students (Navarro Pablo & García Jiménez, 2017; Doiz, Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2014; Sylvén & Tompson, 2015), a fact that can no doubt contribute towards long-term retention of both the subject matter under study and the foreign language through which that subject is being taught. Students are required to process information relating to and arising from two different channels of input (the subject matter and the foreign language), merge the two channels into a single coherent signifier, and then mentally process the resulting combined/dual input into meaningful data. Figure 1 illustrates this mental process (Gimeno Sanz, 2009).

Figure 1 – A CLIL learner’s mental process

3 THE CLIL OPEN ONLINE LEARNING PROJECT

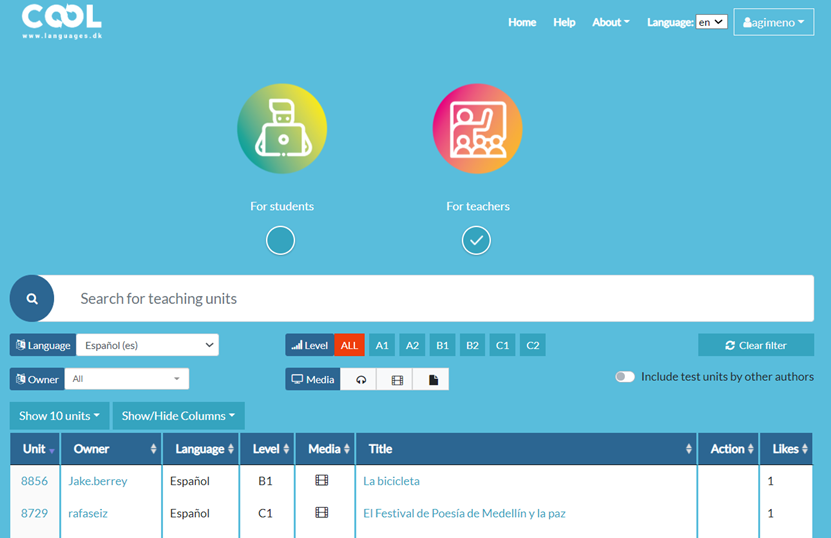

In order to further promote CLIL, the EU-funded CLIL Open Online Learning (COOL) project (2018-2021) has redeveloped and redesigned Clilstore [1] , an online authoring tool to support the implementation of CLIL. Clilstore incorporates two complementary tools, that is, Multidict and Wordlink. Both tools can function as stand-alone resources or within the Clilstore system. Multidict is a multilingual dictionary interface allowing quick monolingual or bilingual searches in over 100 language combinations. Wordlink is an interface that allows users to embed most webpages and link text word-for-word to a selection of curated free online dictionaries. Mre precisely, Wordlink is the software that facilitates the automatic linking of every word in embedded texts within Clilstore learning units and supports learners who wish to easily consult online dictionaries as they read through webpages. Figure 2 illusrates the Clilstore entry page that distinguishes different tools and functionalities according to user profile, that is, teachers or students.

Figure 2 – Clilstore entry page

Clilstore’s features are particularly enhanced when videos and their transcripts are embedded into the system from one of the many streaming video applications currently available, such as TED Talks or Kahn Academy, which offer abundant educational materials in various languages. Because the use of the tool is subject to “CopyLeft” rights, this means that the units and activities created within Clilstore become part of an ever-growing repository that is made freely available to the CLIL and language learning community at large, for learners and teachers alike.

3.1 Clilstore, Multidict and Wordlink

Clilstore is a very simple, yet extremely powerful, authoring tool that allows teachers to create materials based on the integration of streaming video embedded from external sources, any wealth of multimedia elements, links to additional sources and uploaded files, as well as a repository of existing materials. It has been optimized for multiplatform use as well as mobile devices. Because videos are streamed (and never downloaded onto the system), copyright clearance is ensured. The materials that are readily available in Clilstore amount to over 2500 units, covering all six proficiency levels (A1 to C2) of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFRL, 2021) in 68 different languages, and spread over sundry specialised topics (statistics, history, art, economy, biology, chemistry, etc.). Noticably, however, the level of proficiency is determined by the author of the material and may, therefore, be subjective.

Figure 3 – Clilstore menu page

As illustrated in Figure 3, the main menu page allows the user to select student or teacher mode, language and level, to search for specific units, as well as a number of additional search items such as the type of media included in a unit, author, title or topic of unit, the number of views and likes a unit has attracted, and so forth. Although many of the features are common to both access modes (student or teacher), selecting teacher mode enables the user to author new units whereas student mode provises access to the repository of existing learning materials.

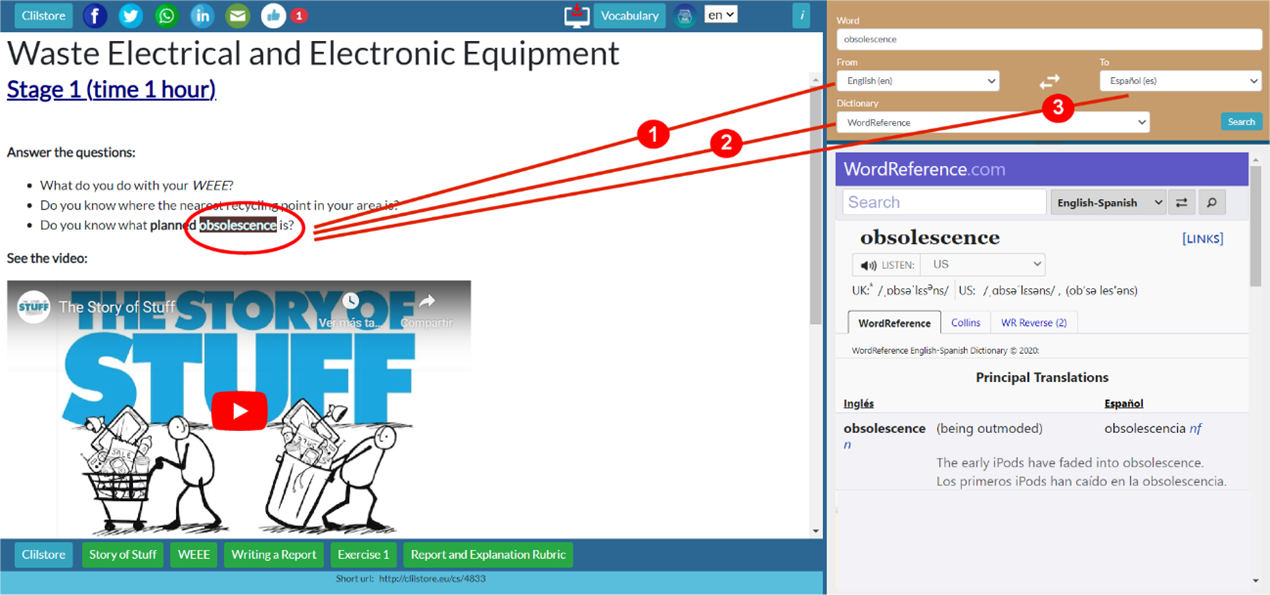

Figure 4 illustrates a view of a unit once it has been selected. It includes an embedded video sequence from YouTube and some comprehension questions. By virtue of Wordlink, all the words in the unit have become automatically linked to a myriad of online monolingual and bilingual dictionaries in different language pairs. In the image we can see that the word “obsolescence” has been clicked on, triggering the Multidict dictionary interface to appear on the right-hand side of the screen. Here the search criteria is displayed for the word being looked up: (1) the source language, (2) the selected dictionary, and (3) the target language for the translation. The author of the unit will have already indicated the source language, so this determines the base language in Multidict. Learners can select the language they wish the search term to be translated into, or if they select for example English to English, they can perform a monolingual consultation. Without having to re-enter the search term, the user can quickly switch between dictionaries using the drop-down menu of available sources (Gimeno et al., 2013).

Figure 4 – The view of a unit in Clilstore

3.2 The Multidict dictionary interface

In a typical situation, where CLIL students are reading an online article in a foreign language, they are very probably going to have to look up the meaning of one or more words. In doing so, students start by opening a new tab, then search for a dictionary, type or paste in the word they need to look up, only to realise that it cannot find the word they are looking for. They end up having to start from scratch, spend time searching the web for another free online dictionary and start the process of typing or copying and pasting the word again. By the time they have finished doing this, and maybe found the translation they were looking for, they may have forgotten the context in which the word was used, so they start reading the text from the beginning in order to find their bearings.

With the Multidict function, this is no longer necessary. At the touch of a button students have access to online dictionaries in over 100 languages, which have been gathered into a single search engine. This gives them quick and easy access to the best dictionaries available on the Internet. Multidict can be used as a standalone regular dictionary by simply typing in the word to be translated or defined, but it also provides immediate access to a wealth of monolingual and bilingual dictionaries should the first search result not be satisfactory.

When used within Clilstore, however, the Multidict interface is automatically linked to the text the learner is reading. This means that the hassle of having to type in a word to find its meaning is no longer necessary. Language learners can simply click on the word and the translation will pop up on the right-hand side of the screen (in default mode). If the word cannot be found, then all they have to do is choose a new dictionary from the drop-down menu. This will save them a considerable amount of search time and make the reading experience easier and smoother, whether they are working on a computer or a mobile device.

There are numerous dictionaries to choose from; some are useful to look up general words and others are more appropriate for specialised fields. For example, the IATE database is a very useful tool if one is working with EU-specific terminology, but it also comes in very handy if one is looking for technical words or terms within most vocational subjects. Another example is the howjsay.com dictionary, which is an audio dictionary of English pronunciation. This is particularly helpful for learners with a lower proficiency level or for those who are unsure of the pronunciation. There is quite an array of dictionaries to choose from although the number varies from language to language. For instance, there are far more dictionaries to and from English than many other language pairs.

The types of users who benefit the most from using Clilstore are most often those who have an intermediate knowledge of the target language. This means that at least a B1 reading level is advisable, especially when working with authentic material. On the other hand, a user who needs to look up every second word will not find Clilstore to much advantage. However, a user who is at a B2 level will be able to successfully read and understand a text that normally requires a C1/C2 level and in a considerably shorter amount of time compared to reading the text without Multidict. Lower intermediate level readers who aspire to move to a B1 level will also benefit from this tool. One of the advantages of Multidict, and Clilstore alike, is that the reader can be exposed to material at a higher level of difficulty. This pushed input with the added support of Multidict can aid the reader in the successful completion of a class assignment or task.

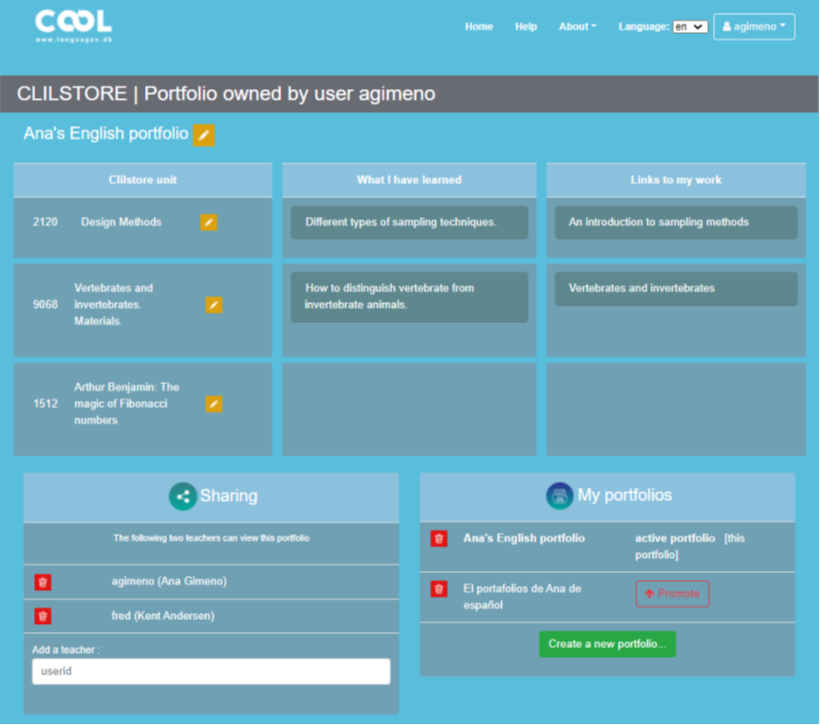

3.3 The Clilstore portfolio

One of the innovations incorporated into Clilstore is its portfolio function. The benefits of portfolios are well documented (Hall & Townsend, 2019; Strasser & Greller, 2014; Mujico & Lasagabaster, 2019). They allow students to a) select materials they have produced that showcase important milestones in their learning trajectory; b) take ownership of their learning through consistently setting goals, reflecting on learning outcomes and other metacognitive processes; and c) develop self-regulation skills that empower them with agency. Self-regulated learning is the ability of learners to control and regulate their own learning through the usage of cognitive and metacognitive strategies (Zimmerman, 2002).

According to Alario-Hoyos (2017), based on Pintrich, Smith, García, & McKeachie’s findings (1993), three categories of strategies have been identified that students should employ to regulate their own learning. These are:

a) Cognitive strategies, which refer to activities that learners utilize in the acquisition, storage, and retrieval of information.

b) Metacognitive strategies, which refer to activities utilized by learners for monitoring and reflecting on their learning process to accomplish a goal.

c) Resource management strategies, which refer to activities that students use to manage their time, study environments, and the resources provided.

In conforminty with these premises, Clilstore has been programmed to include an e-portfolio that encourages learners to set a learning path for a given CLIL subject by automatically adding any Clilstore unit to the portfolio, plus a description of what has been learnt by completing that unit, as well as links to external materials that the learner may have produced (available from a shared Google Drive folder, for instance) as a result of practising that given learning item or skill.

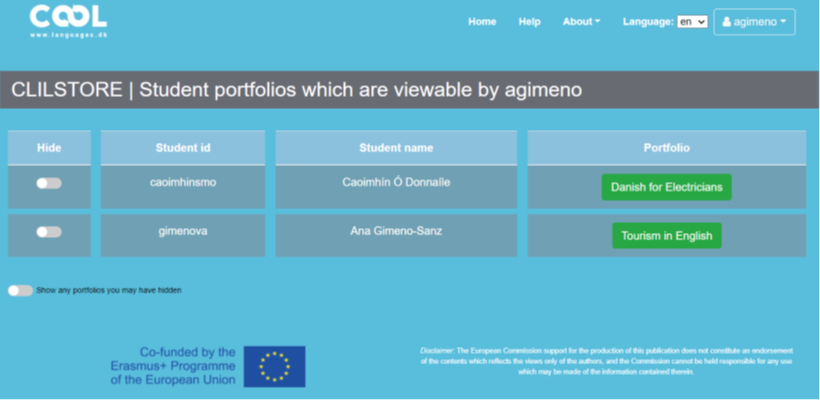

Learners can share a portfolio with their teacher as long as the person is also a registered user of the Clilstore system. This enables teachers to monitor their learners’ progress and, if necessary, to provide feedback.

A learner can create as many portfolios as need be and share them with as many teachers as necessary. It is envisaged that learners may be studying a particular subject matter in a foreign language for their CLIL class and, in addition, a different language as a foreign language. In this case, the learner could create two different portfolios and share them with different teachers. Upon logging in, each of these teachers will be able to see all the Clilstore units and activities completed by a given student, the learner’s own reflection and personal description of what the intake has been and, of course, the links to the other related materials, as illustrated in figures 5, 6 nd 7.

Figure 5 – Sample view of the editable functions of the learner portfolio

Figure 6 – Sample of a teacher’s view of the portfolios to which he/she has been given access by a student

Figure 7 – View of a learner’s portfolio for a given foreign language

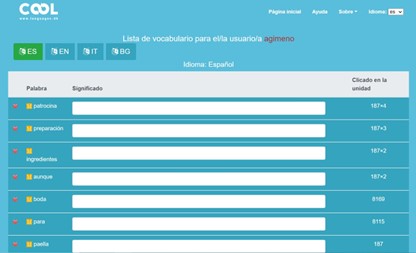

3.4 Creating vocabulary lists

Another of the innovative options available to registered learners on Clilstore is the possibility of creating vocabulary lists. Learners can decide whether to activate or not this function but, in the event that they do, every word that the learner clicks on to look up the meaning in Multidict is automatically registered in a list where the learner can add the meaning (either copying and pasting from one of the dictionaries or through free writing), an item that is particularly useful with words that have several meanings according to context (Figure 8). The learner can also see in what unit a given word was clicked on and how many times, and even go to a given unit by clicking on its unique numerical code. This provides useful information for users because they can infer the difficulty of remembering or not a given vocabulary item.

Figure 8 – Vocabulary lists

4 CLILSTORE AND THE HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY

Among the many disciplines for which Clilstore can prove useful for is the hospitality industry. Hospitality is a broad category of fields within the service industry that includes lodging, restaurants, event planning, theme parks, transportation, cruise lines, and additional fields within the tourism industry. A quick keyword search on Clilstore will reveal a number of ready-made teaching/learning units that could be appropriate for learners of several areas of the hospitality industry. In the first example (Figure 9), there are 3 ready-made activities relating to restaurants at a B1 and B2 level of English.

Figure 9 – Searching “restaurant” as a keyword for learners of English in Clilstore

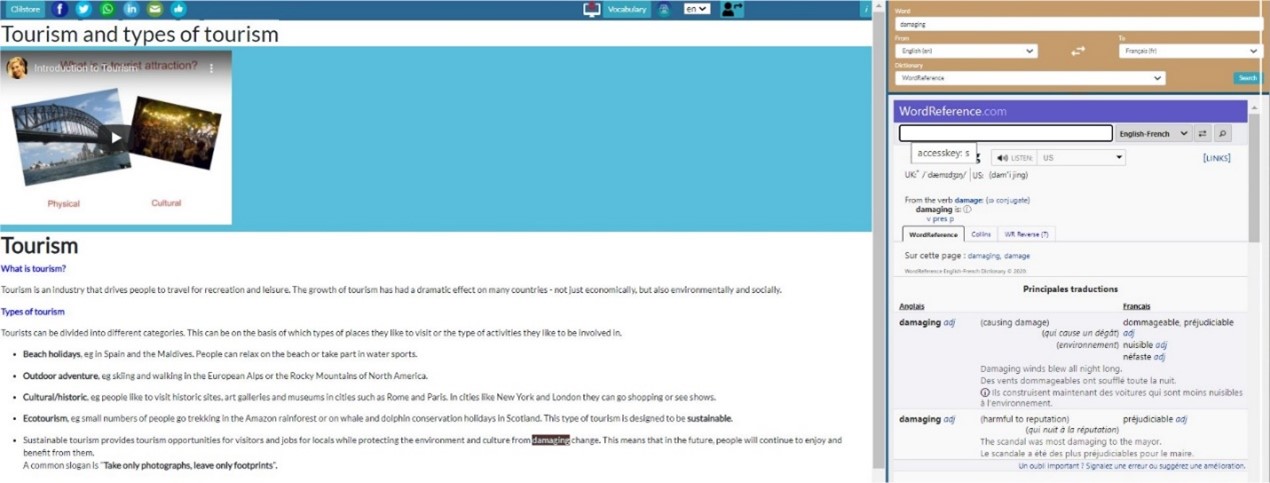

Figure 10 illustrates another example where the keyword “tourism” has been entered as a search item for B1-B2 level learners of English. Users, both learners and teachers alike, uncover a Clilstore unit describing the different types of tourism and several comprehension activities accompanying it.

Figure 10 – Tourism activity for learners of English.

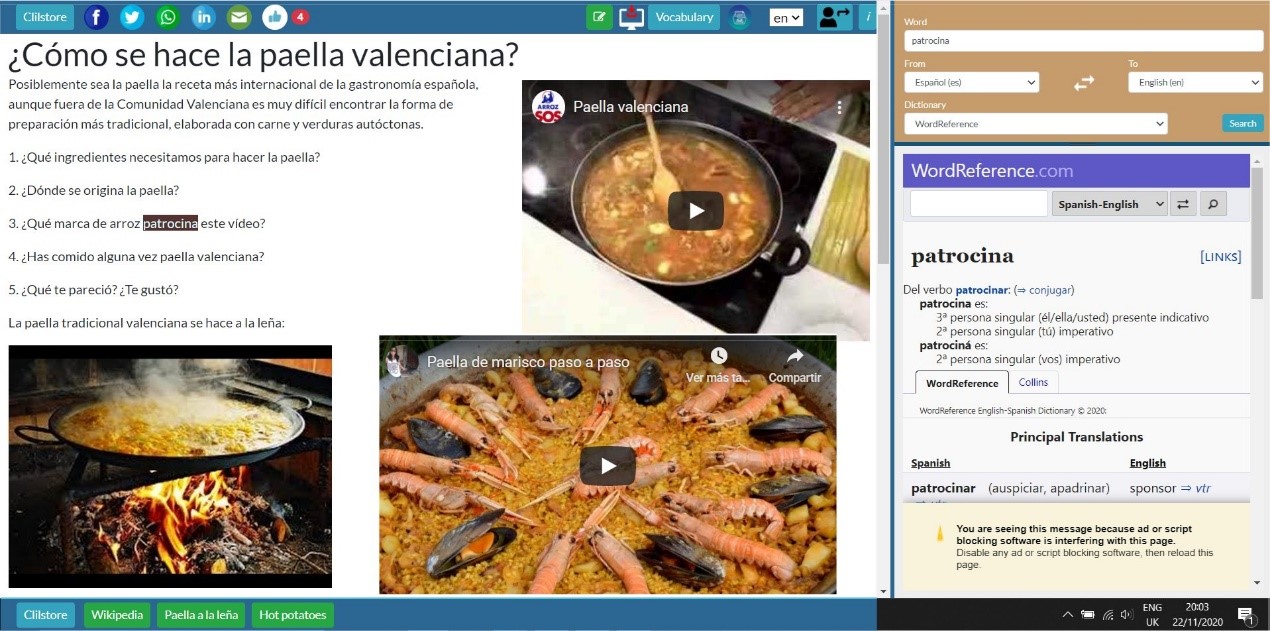

Within the topic of cuisine, another example can be found when searching for specific international dishes. Figure 11 displays an activity based on cooking the traditional Valencian dish, the “paella valenciana”. The activity includes a video-comprehension exercise focusing on the language of instructions and food-related vocabulary in Spanish.

Figure 11 – Activity relating to national cuisine for learners of Spanish

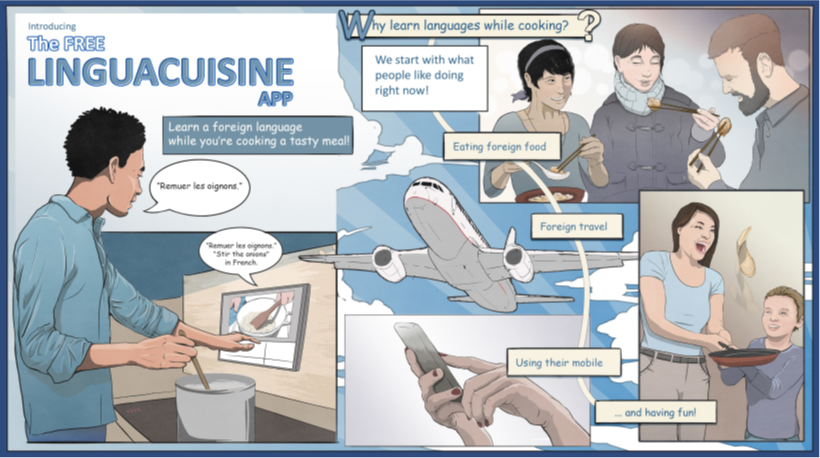

5 THE LINGUACUISINE PROJECT: A COOKING-BASED LANGUAGE LEARNING APPLICATION

The Liguacuisine project, coordinated by Prof. Paul Seedhouse from Newcastle University (UK), produced an app that can be downloaded from https://linguacuisine.com. The app is based on the principles underlying Task-Based Language Learning and Teaching (TBLT), whereby students are prompted to achieve a non-linguistic goal or complete a non-linguistic task through using the target language in a holistic way. These goals or tasks are generally carried out in pairs or groups aiming to favour learner autonomy, learner interaction and collaboration. According to Seedhouse et al. (2019),

[Firstly, students use the foreign] language to complete a culinary task, rather than focusing primarily on the language itself. Secondly, learners must employ all four language skills in a holistic manner to achieve the task. Thirdly, the task is situated in an authentic real-world context, namely the kitchen. The task is goal-oriented, involving the production of a dish. Fourthly, cooking tasks are carried out in pairs. […] Finally, learners can measure their own success by non-linguistic goal completion, through cooking and consumption of the food. A further characteristic of the Linguacuisine task is that it is a focused task, in that it is necessary for learners to recognise the spoken form of named L2 vocabulary items in order to carry out the task (p. 78).

Further to these observations, the authors adopted the cyclical pedagogic framework put forward by Skehan (1998) and Ellis (2003), which divides the completion of a task into three stages, that is, the pre-task (preparation stage), the during-task (performance of the main task), and the post-task (reflection on and evaluation of what has been learnt through the main task).

Two empirical studies (Seedhouse et al, 2019) to determine the language learning gains of the app (Chinese and Vietnamese) demonstrated that vocabulary acquisition had been significant. Another empirical study allowed the authors to establish what the learners’ overall attitude was with regard to the learning process, and whether using the app had helped them improve their digital competencies. They concluded that there had been significant gains in areas such as “information and digital literacy”, “information and data literacy”, “communication and collaboration”, and “digital content creation”, albeit not to a significant degree.

The Linguacuisine project was the successor of a previous European-funded project (LanCook -Learning Languages, Cultures and Cuisines in Digital Interactive Kitchens) that developed language learning materials for European languages and cuisines: English, German, Spanish, Catalan, Italian, French and Finnish. They produced the French and European Digital Kitchens to promote situated learning . The materials are housed in a ‘mobile kitchen’ where, via a tablet PC, the kitchen communicates with learners and instructs them in how to cook a typical dish of one of these seven languages. Figure 12 illustrates the entry page to Linguacuisine.

Figure 12 – The Linguacuisine App

6 CONCLUDING REMARKS

CLIL has been proven to be a useful dual focus methodology for various educational sectors and age groups (Papaja, 2012; Aguilar & Rodríguez 2012). It requires learners to make the additional effort to assimilate content delivered in a language that is foreign to them in such a way that the target language does not interfere with content learning, but rather enables it. As has been demonstrated, there are a number of tools and resources currently available that are particularly useful in order to implement CLIL. Not only have many studies proven the methodology’s worth, a number of them have also proven that, despite its challenges, on the whole learners find this method motivating and satisfactory (Lasagabaster, 2011; Sylvén & Thompson, 2015; Pladevall-Ballester, 2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the European Commission for co-funding the CLIL Open Online Learning (COOL) project from 2018 to 2021 (ref. KA2-2018-1-ES01-KA203-050474).

Notes

[1] Clilstore was first launched as a result of the Tools for CLIL Teachers project (Ref. 517543-LLP-1-2011-1-DK-KA2-KA2MP).

Références bibliographiques

References

Aguilar, M., & Rodríguez, R. (2012). Lecturer and student perceptions on CLIL at a Spanish university. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(2), 183-197.

Alario-Hoyos, C., Estévez-Ayres, I., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Kloos, C. D., & Fernández-Panadero, C. (2017). Understanding learners’ motivation and learning strategies in MOOCs. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(3), n.p.

Carrió Pastor, M.L.& Gimeno Sanz, A. M.(2007). Content and Language Integrated Learning in a Technical Higher Education Environment. In Diverse Contexts - Converging Goals. Content and Language Integrated Learning in Europe (pp. 103-111). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clilstore (2014, updated 2020). http://clilstore.eu/

Darn, S. (2006). CLIL - A European Overview. Available from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED490775.pdf.

Doiz, A., Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J.M.(2014). CLIL and motivation: the effect of individual and contextual variables. The Language Learning Journal, 42(2): 209-224, DOI: 10.1080/09571736.2014.889508.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based Language Learning and Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gimeno, A.; Ó Dónaill, C. and Zygmantaite, R. (2013). Clilstore Guidebook for Teachers. Available from http://www.languages.dk/archive/tools/guides/CLILstoreGuidebook.pdf

Gimeno-Sanz, A.M.(2009). How can CLIL benefit from the integration of information and communications technologies? In Content and Language Integrated Learning: Cultural Diversity (pp. 77-102). Bern: Peter Lang.

Gimeno-Sanz, A. (2021). Integrating CLIL in Education: Exploring Teachers’ Perceptions toward Using a Dedicated Online Tool. Verbeia Monográfico, Año V, Número 5, pp. 10-25.

Gimeno-Sanz, A., Ó Dónaill, C., and Andersen, K. (2014). Supporting content and language integrated learning through technology. In CALL Design: Principles and Practice-Proceedings of the 2014 EUROCALL Conference, Groningen (pp. 107-112). Research-publishing. net.

Hall, J., & Townsend, S. D.(2019). Developing a Theory of Practice for CLIL with Pre-service Teachers. Journal of the Japan CLIL Pedagogy Association, 1, 176-194.

Mujico, F. G., & Lasagabaster, D. (2019). Enhancing L2 Motivation and English Proficiency through Technology. Complutense Journal of English Studies, 27, 59-78.

Navarro Pablo, M. & García Jiménez, E. (2017). Are CLIL Students More Motivated? An Analysis of Affective Factors and their Relation to Language Attainment. Porta Linguarum, 29, pp. 71-90. https://www.ugr.es/~portalin/articulos/PL_numero29/4_MACARENA%20NAVARRO.pdf

Kahn Academy https://www.khanacademy.org

Lasagabaster, D. (2011). English achievement and student motivation in CLIL and EFL settings. Innovation in language Learning and Teaching, 5(1), 3-18.

Marsh, D., Marsland, B., & Stenberg, K. (2001). Integrating Competencies for Working Life. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Papaja, K. L.(2012). The impact of students’ attitudes on CLIL. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 5(2), 28-56.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J.(1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and psychological measurement, 53(3), 801-813.

Pladevall-Ballester, E. (2019). A longitudinal study of primary school EFL learning motivation in CLIL and non-CLIL settings. Language Teaching Research, 23(6), 765-786.

TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) http://www.ted.com

Seedhouse, P., Heslop, P., Kharrufa, A., Ren, S., & Nguyen, T. (2019). The Linguacuisine Project: A Cooking-Based Language Learning Application. The EuroCALL Review, 27(2), 75-97.

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Strasser, T., & Greller, W. (2014). Towards digital immersive and seamless language learning. In European Summit on Immersive Education (pp. 52-62). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22017-8_5.

Sylvén, L.K.& Tompson, A.S.(2015). Language learning motivation and CLIL. Is there a connection? Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 3(1): 28-50. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.3.1.02syl.

Zimmerman, B. J.(2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into practice, 41(2), 64-70.