‘Do you speak English?’ ‘Are you working me?!’ Translanguaging practices online and their place in the EFL classroom: The case of Facebook

Christopher LEES, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Résumé

Cette publication enquête sur l’usage du translanguaging sur Facebook de la part de quinze élèves grecs du secondaire. Ainsi, cette étude met en évidence comment ces jeunes grecs ont fait preuve de créativité dans l’utilisation des langues avec lesquelles ils sont en contact et comment ils prennent appui (ils se basent) sur elles afin de communiquer sur internet avec leurs semblables (leurs camarades). De plus, l’article analyse la mesure dans laquelle la communication en ligne est présente dans le matériel didactique en Grèce et comment cet apprentissage centré autour de la grammaire ne permet pas aux étudiants de développer un sens critique qui leur permettrait de comprendre la langue dans sa réalité et complexité discursive. Enfin, j’explique que l’intégration (qu’intégrer, proposer/la proposition, assimiler, introduire) de pratiques de translanguaging, telles que celles présentées dans ce document, contribue à développer la capacité des étudiants à comprendre la langue étrangère et à communiquer de façon plus fluide (naturelle) avec les autres. Enfin, je suggère des moyens pour y parvenir dans les classes de EFL (Anglais Langue Etrangère) des écoles secondaires.

Enseignement dans le secondaire - Ethnographie sur internet - Facebook - Prise de conscience critique de la langue - Translangage

Abstract

This paper examines the translanguaging practices of fifteen Greek secondary school pupils on Facebook. In doing so, it highlights the creative ways in which young Greek people demonstrate the varieties of language with which they come into contact and how they build on these to achieve their communicative goals with their peers online. Moreover, the article discusses the extent to which online communication is present in current teaching material in Greece and how the grammar-oriented approach adopted does not contribute to learners’ critical awareness of context-based language use and variety. Finally, I argue that integrating translanguaging practices such as the ones presented in this paper contribute to pupils’ critical language awareness of how the boundaries between various languages are often fluid in their own interpersonal communication and I suggest ways in how this can be achieved in the secondary school EFL classroom.

Critical language awareness - Facebook - Online ethnography - Secondary school education - Translanguaging

1. Introduction

Translanguaging in online communication and its sociopragmatic features and functions are subject to the same constraints as other examples of language diversity in foreign/second language teaching, such as dialects and sociolects; we know they exist, but we don’t talk about them in the classroom. As Bella (2012, p. 2) points out in her work on increasing pragmatic awareness in learners of Greek as a foreign language, “despite the fact that pragmatic awareness and cultural appropriateness are considered important, they continue to take a back seat to grammaticality in classroom practices.” This is certainly true of the EFL context in Greece, where different varieties of language used in everyday communication are almost entirely absent from the teaching material used in schools. If they are present, emphasis is, as Bella notes, placed on grammatical features as opposed to the communicative functions such examples of language use have for those who use them. In other words, despite current trends in foreign language teaching favouring a communicative approach, whose purpose is to present and use language in a way that reflects communicative goals in real contexts as opposed to focusing on grammatical forms (Lightbown & Spada 2006, Bella 2011, Galantomos 2012), language teaching material in Greece continues to revolve around formal grammatical features of the standard language.

In this paper I shall argue that including language variation in the classroom is desirable, not only able to enhance the learner’s critical awareness of how language is used in various instances of communication, but also to better equip them for the realities of how language is used in real-life contexts. In particular, I shall focus on how the translanguaging practices of teenagers on Facebook could be incorporated into EFL classes at secondary school level. However, before this is done, two issues arising from the discussion so far should be clarified: Firstly, the ways in which foreign language elements that appear in another language are approached and analysed should be outlined and discussed; and secondly, the reasons why translanguaging in learners’ own communication on Facebook could be useful to language learning should be put into context.

In relation to the first issue, any instance where elements from a foreign language occur in another language is a result of language contact. In the past, this was understood to take place through the geographical movement of peoples from one place to another, either out of free will for reasons of migration or out of force, for example during colonial times, where the customs and language of the dominant group were imposed on the people being colonised (Skutnabb-Kangas 1999, Mesthrie et al. 2000, Thomason 2001). Today however, both socio-political and technological developments have dramatically changed the ways and speed with which languages come into contact with each other. For example, just as advancements in medicine and astronomy in antiquity saw many Greek terms being adopted by other languages as a way to express concepts formulated in other cultures, so too have many technology-related terms coined in English-speaking countries been incorporated into other languages, either as they are or as loan translations (Bakakou-Orfanou 2005).

With particular reference to Greek, many English words found their way into the language due to the possibilities they afforded speakers to more accurately express certain cultural phenomena developed in rapidly evolving sectors, such as technology and fashion (Makri-Tsilipakou 1999a, p. 449). These loans are referred to as cultural borrowings (Myers-Scotton 1992, cited in Makri-Tsilipakou: ibid, p. 449). However, cheaper air travel together with a variety of educational and professional exchange programmes mean that people and their languages come into contact with each other at a much faster and varied pace than they did in the past. Furthermore, it is no longer necessary for this contact to occur physically, as the last decade has also seen the revolution of the internet and the emergence of what Androutsopoulos (2013b, p. 236) terms the participatory web era, in which people from every corner of the globe are able to come into contact with each other online and communicate in both synchronous and asynchronous settings. This new form of contact has led to different uses of foreign language elements, which go beyond single-word terms and include entire phrases or even novel phrases which do not correspond to the way language is used by native speakers. As a result, in the past twenty years, attempts have been made to classify this creative mixing of language elements. It is in this context that the term and concept of translanguaging has been developed.

Translanguaging as a concept is largely attributed to the work of Ofelia García in bilingual education (2009) and refers to the often creative ways in which speakers of different languages use resources from their respective languages as part of an integrated system of communication, whereby features of various languages are combined to communicate meaning and experience from the perspective of the speaker (Tsokalidou 2015, p. 390). Moreover, the very nature of translanguaging breaks down the structuralist, “wholesale” view of language as a limited set of defined features (Androutsopoulos 2013a, p. 186, Tsokalidou & Koutoulis 2015, p. 163) and provides a framework in which the fluidity of language can be observed and understood, through which speakers draw on their multilingual resources to navigate and express meaning in a way that reflects their own multilingual and multicultural identities (ibid). For example, a person of Greek origin living in an English-speaking country may combine elements of Greek and English, both as a way of emphasising or better expressing cultural elements that may not be as easily expressed in the host country’s language, or to index, whether consciously or subconsciously, the dual identity of the speaker themselves (see Tsokalidou 2006, 2015).

Social media such as Facebook are also dynamic multilingual meeting places, where users engage in translanguaging practices. This, together with the fact that they make up part of young people’s everyday communication, makes them an interesting case study for language variety and education. For example, Androutsopoulos (2013a) has shown how pupils of Greek origin living in Germany mix Greek with German and English in their communication on Facebook, German being the language where their experiences at school can be expressed and Greek being a way to express their identity of origin. Moreover, highly creative words where novel expressions are often formed involving features from more than one language. Similarly, Sharma (2012) has shown how students from Nepal use English, which is not their mother tongue, on Facebook, so as to align themselves with a progressive, modern and cosmopolitan identity, even in interpersonal communication with fellow students, where the use of Nepalese would be expected. In this paper, we will see examples from my own research (Lees 2017), which show how Greek secondary school pupils with no immigrant background use English and Greek together in their own interpersonal communication to perform a variety of communicative functions, such as amusing each other, conveying practical information from English-speaking contexts, and indexing identities.

As highlighted earlier, the second issue that should be clarified before further discussion on how Facebook translanguaging practices are brought into the classroom is why this should be considered beneficial to language education. Firstly, it should be noted that scholarly discourse concerning language variation, the broader category to which translanguaging practices in social media such as Facebook belongs, and its incorporation in language teaching, is not new. For example, there is an increasing debate in the literature as to how regional, global, and social varieties of English should feature in language instruction at the local level (Beiswanger 2008, Davydova et al. 2013, Illés & Akcan 2017). Furthermore, the emergence of a variety of new literacies in the wake of the technological revolution, including children’s out-of-school online practices, has brought about the need to explore the characteristics of these new literacies and how they can and should be used in education (Street 1993, Cope & Kalantzis 2000, Gee 2004) [1]. What followed from this was the formulation of the Home-School Mismatch Hypothesis (Stamou et al. 2016, p. 15). According to this hypothesis, a chasm has developed between the type of language children are taught in school and the type of language they are using at home, meaning that language used at home is often very different to how it was used and taught in school (Koutsogiannis 2009, Bulfin & Koutsogiannis 2012). Unfortunately, the scope of this paper does not allow for an elaborate discussion on the background and various positions on new literacies [2]. However, what is important to say is that there is general agreement in linguistic scholarship, particularly in the field of critical literacy, that exposing learners to varieties, genres, and new types of literacies is in the interest of fostering metalinguistic awareness (Tsiplakou, Ioannidou & Hadjioannou 2018, p. 62-71). Moreover, despite the fact that children’s out-of-school literacy practices are generally excluded from language teaching, research shows that they are by no means inferior to those which currently feature in the classroom (Stamou et al. 2016, p. 5).

Regarding the benefits of using translanguaging practices in particular in the language classroom, aside from raising critical awareness of the interconnection between language and identity (Tsokalidou 2015, 2017), using translanguaging in class can also help strengthen learners’ weaker language (Baker 2001, cited in García & Wei 2014, p. 64) by using the one language to explain content discussed in the other. Moreover, Tsokalidou and Koutoulis (2015, p. 164-165) highlight that translanguaging enables speakers to be creative in constructing and navigating meaning through the use of more than one language, thus further enhancing their critical skills. As a result, it is hoped that the proposals put forward in this paper will contribute to satisfying two objectives in current research on language variation: bringing children’s out-of-school language practices into the Greek language classroom and raising children’s critical awareness of the symbolic and fluid nature of language in online communication settings.

In the next section of the paper, the extent to which online digital communication features in Greek secondary school textbooks will be presented and discussed before the results from the study are presented and proposals put forward regarding how the translanguaging practices shown here could feature in language education in Greek secondary education.

2. Online communication in Greek secondary education teaching material

In this section, an overview of the extent to which online communication is present in the teaching material used in Greek state secondary education will be presented and discussed. As Tsokalidou and Koutoulis (2015, p. 164) note:

As far as Greek society and education is concerned, bilingualism is predominantly non-existent; politically, ideologically and linguistically. In other words, there is an absence of any language other than Greek as a means of communication (my translation).

I would like to expand on this position by saying that while the learning of foreign languages -currently solely Western European languages [3]- takes places and is encouraged in state education in Greece, it is bilingualism or the “mixing” of languages that is absent or, as we will see in this section, discouraged in state education. One potential reason of this could be that textbooks used in Greek state education are written and published under the supervision of the Greek Ministry of Education. Therefore, if as Tsokalidou and Koutoulis (ibid.) suggest, there are political and ideological forces at work that do not wish to encourage bilingualism; these “agenda” could very easily be pushed if the state has control over the books which are used in education. To highlight this, although this section will deal with the extent to which online communication is represented in EFL secondary school textbooks, I would like to begin the review of online communication in Greek teaching material by presenting an example from the textbook used in Greek language classes for pupils in their third class of Greek gymnasio (Katsarou et al. 2012, p. 36), equivalent to Year 10 in UK secondary education. I choose this example, because I believe it provides a context that explains why online communication and translanguaging are absent from current teaching material, as well as the position of Tsokalidou and Koutoulis (2015, p. 164) that Greek is the sole means of communication in the country, while foreign languages such as English are presented and taught as “foreign,” not to be mixed with Greek.

The text in question uses an article by Titika Dimitroulia published in the Greek newspaper, Eleftherotypia in 2002 (cited in Katsarou et al. 2012, p. 36), which refers to how the presence of English on the internet should be of no concern to the Greek language. However, the way in which the article has been appropriated in the textbook for the purpose of language activities suggests the exact opposite. Firstly, the underlining of two sections of the text directs the pupil’s attention to concerns referred to in the text as to whether “Greek internet users’ continued use of English may distort Greeks’ linguistic intuition and, by extension, the language itself” (my translation) and to the sentiment that the use of Greeklish [4] may result in the Greek alphabet being replaced by the Latin script (ibid.). This, in theory, could actually be ideal for stimulating a lively in-class discussion on whether such notions hold true and who, when, and how English may be used in combination with Greek online. It is also worth noting that the article, along with the book itself, are several years old and, therefore, lack a current up-to-date perspective on online communication. This gap could easily be bridged by children’s knowledge of computer technology and online communication and would be in keeping with current trends on focusing on pupils’ own day-to-do communication practices in education (Koutsogiannis 2012, p. 215). As opposed to this, the activities suggested ask pupils to restate the message that the underlined sections of the text in particular wish to convey before proceeding to make a note of the verbs and adjectives used, to think and note down their synonyms and then to write two of their own phrases using the words they have noted down.

In short, it would seem that the purpose of the exercise above is to instil in children a sense of fear concerning the “dangers” of using English together with Greek online and to encourage them to reiterate this in their own words. It is also worth noting that no attention is paid to the socio-pragmatic aspects of language use online, or to critical thinking. There is also reference in EFL books to the danger of using abbreviations, both in Greek and English, specifically in the workbook used for advanced learners of English in Year One (Karagianni et al.c 2009, p. 118), where pupils are asked to express their opinion on whether young people using abbreviations in online communication could be considered dangerous for their language.

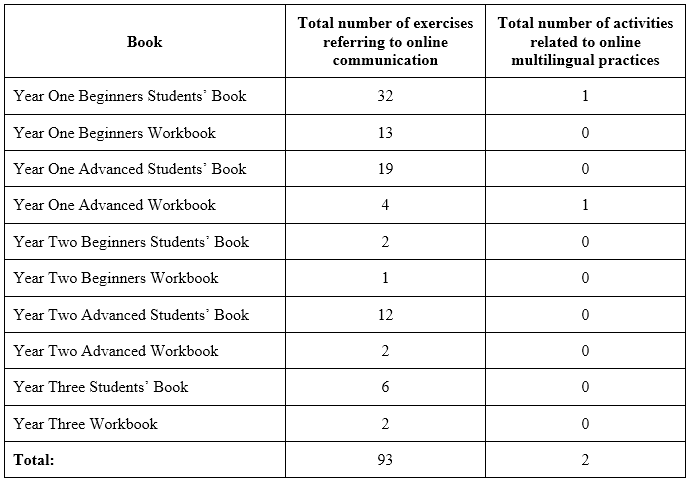

As we shall now see, despite the fact that reference is made to online communication in Greek secondary school EFL books, the material also falls short of enhancing pupils’ critical awareness of the sociopragmatic function of language use in online communication settings. To be more specific, a total number of ten textbooks, which have been composed under the supervision of the Greek Ministry of Education, are used at secondary (Greek Gymnasio) level: one pupils’ textbook and one exercise book for “beginners” and “advanced” pupils in Years 1 and 2 and one pupils’ textbook and one exercise book for Year 3, which does not distinguish between “beginners” and “advanced” learner. All books were manually analysed by applying a qualitative content analysis (Weber 1990, Krippendorf 2004). The purpose of this was to ascertain which activities were related to online communication and multilingual communication practices online. In light of this, references to online environments, such as the internet, as tools for researching information were excluded, whereas their role in facilitating communication, i.e. an exchange between two or more people, were included. The analysis yielded some quantitative results that are shown in Table 1 below. It should also be clarified that all books feature main activities and related secondary activities, for instance 1; 1.1; 1.2 etc. Instances where reference is made to online communication or multilingual communication practices were recorded per exercise and not per token. The reason for this is related to an interest in how many activities deal with online communication and multilingualism, as opposed to how often words related to it are used.

Table 1: Instances of reference to online communication and online multilingual practices in Greek secondary school language

It is clear from the data presented in the table that, albeit unevenly distributed in the material, a concerted effort has been made to include aspects of online communication in EFL textbooks used in secondary school. For example, exercises in all books in all classes often ask pupils to read and write emails as opposed to more traditional texts, such as letters, thereby including new forms of literacy (Cope & Kalantzis 2000). However, as mentioned above, a qualitative study of the material reveals that where reference is made to communication online, the focus of the activity is, overwhelmingly, on understanding and producing the text or its grammatical features, whereas no attention is drawn to the structure of the text, the linguistic features or the interpersonal relations of those engaged in the communicative act. The result of this is that learners do not critically engage with the text, its linguistic and communicative features, and how it may differ from other texts.

Let us take the example of Activity 1 on page 20 of the students’ book used in Year One for beginners (Karagianni et al. 2009). Pupils are asked to refer back to an email presented on page 18, in which Helen replies to an email sent to her by Pablo, an exchange student who is planning to visit Greece. Activity 1 then asks pupils to find the plural forms of a selection of nouns that are used in the email. Moreover, the nouns in question are simple everyday words such as city, house and church; in other words, nothing associated with interpersonal online communication. In this sense, it could be argued that the fact the text presented is an email is irrelevant to the learning outcome of the activity; put simply, the text could easily have been presented in the form of a letter without affecting the nature of the exercise in any way. This point supports Bella’s claim (2012, p. 2) that the primary focus of language material is on grammaticality, even though the material included in the EFL textbooks could lead to a highly engaging critical discussion on aspects of language and online communication. In reality, there are only very few exceptions to this, such as Activity 4 on page 78 of the Students’ book used for advanced learners in Year Two (Giannakopoulou et al. 2009), where acronyms used in text messaging are presented and pupils are asked to match their meanings to corresponding full formed words or phrases and to create their own “digital dialogues” with their friends. Similarly, another example of an activity which engages pupils with online communication is in the workbook used in Year 1 for beginners (Karagianni et al. 2009, p. 12). More specifically, pupils are asked to read an email sent from a pupil to the members of his e-group. They are then asked to fill in the gaps by choosing the most suitable expression from a list of informal expressions provided.

Activities such as those outlined above are highly significant as they expose pupils to different varieties of language and encourage them to reproduce them in authentic settings. In this sense, such activities are in line with the communicative approach to language teaching, but also with critical literacy. Despite this, however, the overwhelming majority of activities in all books centres around grammar and reading comprehension with very little attention being drawn to the linguistic and communicative aspects of online communication. Indeed, this is even more apparent in the case of multilingual communication practices online with just two instances in all the EFL books used in Greek secondary schools altogether. The first instance occurs in Activity 1 on page 50 of Year One’s beginners’ students’ book (Karagianni et al., p. 2009). An email from a pupil is presented which includes the word recycling. Pupils are asked to identify the “Greek word in this English word.” Although this exercise is useful in highlighting examples of lexical borrowing in established words and phrases (see Makri-Tsilipakou 1999b, Bakakou-Orfanou 2005), it does not deal with the ways in which speakers use various features of the languages they possess to convey meaning. In this sense, the activity perpetuates the view of language as a “wholesale” entity (Androutsopoulos 2013a, p. 186). The other example is from the workbook used for Year One advanced learners (Karagianni et al., 2009, p. 118). More specifically, Activity One asks pupils to think of English and Greek abbreviations when communicating via text messages. They are then asked to express their opinion as to whether or not this is dangerous for the language as a whole. The positive aspect of this activity is that it encourages pupils to think of how Greek and English are used online and to engage in a critical discussion of whether this could in fact be detrimental to the language. As a result, as opposed to the example we saw earlier from the textbook used for Greek language classes (Katsarou et al. 2012, p. 36), pupils are encouraged to engage with the topic of discussion and formulate their own opinions. They are also encouraged to use out-of-school language practices in school discussion, which, as we saw earlier, is supported by current thinking in language teaching (Street 1993, Cope & Kalantzis 2000, Gee 2004).

In conclusion, while it would not be fair to say that EFL material in Greek secondary schools makes no effort to include modern forms of literacy in language classes, it is clear that there is a considerable lack of focus on the sociopragmatic aspects of language use in online settings. Moreover, the almost exclusive emphasis on e-mail as a form of online communication shows how outdated and irrelevant the material is for young people today, who more than likely would not use email to talk with their friends, but one of the various social media such as Facebook or Instagram. Likewise, multilingual online communication practices are almost entirely absent from the teaching material, thus continuing to present languages such as Greek and English as separate entities, despite the fact that evidence shows (see Sharma 2012, Androutsopoulos 2013a, Lees 2017) that young internet users frequently mix languages, often in highly inventive ways. The following section will present the data sample and methodology used for my own research into how Greek secondary school pupils use English in their communication on Facebook.

3. The study and methodology

The study from which the data which will be presented here derives is part of my doctoral research, which investigated the online language practices of fifteen Greek secondary school pupils on Facebook. The participants comprise students from two experimental schools [5] in the Greek city of Thessaloniki. Of the total number of pupils, nine were girls and six were boys; a combination of both sexes was desirable in order to observe any noticeable communication or linguistic differences between the two groups. A presentation was carried out in both schools, during which the aims and participant obligations were outlined and names of those willing to participate were collected. Moreover, in line with online research ethics (D’Arcy & Young 2012, Androutsopoulos 2014), a pseudonym was assigned to each participant in the interests of anonymity, real names were not featured in any research-related publications and work, while parental/guardian consent was sought and obtained for each pupil. Regarding the obligations of the participants, it was explained that they would need to provide me, the researcher, with access to their Facebook wall posts and comments so as to follow and interpret their data, which would remain anonymous. In addition to this, it was explained to them that they would be required to participate in interviews related to the content of their comments. All pupils were informed that their participation was entirely voluntary and could be terminated at any time. Generally speaking, a concerted effort was made to create a comfortable atmosphere for the pupils and to minimise the presence of the researcher so as to avoid what Labov (1972) terms observer’s paradox, in which the researcher’s overbearing presence can have a negative impact on the authenticity of the data elicited. As such, it was important that pupils felt comfortable using language as they normally would, as if I were not there.

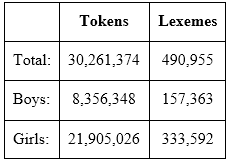

After consent was received, a research profile was created by myself on Facebook and friend requests sent and accepted by the fifteen pupils. Following this, a corpus of back-dated data was made, so as to include the six-month period of October 2013 to March 2014. The reason why this period was selected for analysis was that it included the start of the school year and the Christmas holidays, times when Facebook activity was predicted to be particularly high. The corpus was compiled by opening all posts and comments and storing them as pdf and html text files, in order to allow for corpus software processing. The size of the total corpus is presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Tokens and lexemes (Lees 2017: 69)

As can be seen from the corpus, the vast majority of language produced on the Facebook profiles analysed is attributed to communication on the girls’ walls. As my research indicates (Lees 2017), boys generally write less than girls do, the latter using language as a way to display friendship and solidarity with each other (see Coates 1997, 1999), whereas boys use language for descriptive or informative purposes.

The data set relating to translanguaging practices in particular forms part of my research that looked at how the pupils use English in their online communication on Facebook. The analytical framework used for the data was that of online ethnography advocated by Androutsopoulos (2014), which includes observing participant activity online and establishing contact with informants to discuss phenomena observed which may not be clear to the researcher. It should be noted that this approach differs from the traditional approach to the ethnography of communication founded by Hymes (1962) in that as opposed to spoken language in live contexts of communication, the researcher observes language practices between members of a group he/she has not direct contact with. In this sense, much of what is said online may be based on shared knowledge between participants in other [live] aspects of their lives. This presents a challenge for the researcher, who must be able to observe, understand interpret the ways in which online participants communicate. To this end, Androutsopoulos’s suggested blended data (Androutsopoulos 2013b, p. 242) has the advantage of being able to directly contact participants to help interpret their own language practices as observed in their online communication. Such an approach is invaluable in making sense of what can be dynamic and rich language practices linked with various aspects of the participants’ shared knowledge and identity, to which the researcher is not privy. In my research, this direct contact with participants took place either by means of a scheduled live interview or through use of private messages on Facebook itself.

Finally, owing to the relatively small data sample from which no reliable statistics can be derived, together with the fact that various categories of multilingual language analysis overlap, e.g. translanguaging, code switching, alphabet alternation and the use of English terms from various sources, it is felt that a qualitative approach would be much more valuable in order to examine the various ways in which the participants under study make use of their resources in Greek and English in their online communication, ways that would not be best represented in terms of figures and statistics. Therefore, the data presented in the following section will be qualitative.

4. Translanguaging practices on Facebook

From the qualitative analysis carried out after observing the language practices of the 15 school pupils over the six-month period from October 2013 to March 2014, it became clear that English was almost the sole choice of language other than Greek to be used. There were a few isolated uses of German, but by far the most substantial and creative use of translanguaging occurred through a combination of Greek and English. The reason behind this use of English can be explained by the fact that English is the first and most widespread foreign language learned in Greece in both state and private education (see Boklund-Lagopoulou 2003). In addition, young Greeks attend private language institutions, in order to prepare for exams in language proficiency, which is required for the majority of skilled employment in the country. Moreover, the sociolinguistic background of the pupils must be taken into account; the participants in my research were all native Greek speakers with no immigrant background. Therefore, as opposed to participants in studies such as Androutsopoulos (2013a), whose background meant that in addition to the language of the host country, they were also speakers –at varying levels- of the language of their country of origin, the participants in my research have a shared first language and a shared second language, English.

However, as opposed to merely being a language of instruction in school, young Greeks are also exposed to English from a variety of other sources such as video games, films, music, and social media. The combination of these factors means that English represents a common code of communication which, albeit a foreign one, represents their own experiences of being young in Greece. As Androutsopoulos (2004, p. 84) notes, “the formation and development of youth cultures in Germany (and probably in other parts of the world) is dependent on English-speaking pop culture.” As we will see below, translanguaging with Greek and English on Facebook is, in the case of my data, a manifestation of the shared identity the participants have of being Greek pupils who learn English in formal education, but also engage with English-speaking popular culture.

In my data, two main grammatical patters can be observed in relation to how the fifteen participating pupils used Greek and English in their communication on Facebook. Firstly, comments written in Greek were interspersed with words or phrases in Greek, which demonstrated the contact participants had with aspects of English-speaking popular culture; secondly, larger segments of English were embedded into messages written in Greek or interspersed with Greek words or phrases. Examples 1, 2 and 3 are indicative of the first trend.

1. BROS [...] KAI [...] 1 WIN AKOMA KAI KSANAPAO PROMOTION

Bros [...] and [...] 1 more win and I’m going to get another promotion2. To kalitero dwro ever! Thanx bro

The best gift ever! Thanx bro3. Αχιλλέας: Τι σου ειπα εγω το μεσημέρι? Κοπυ το εκανεσ

Φωτεινή: Αχιλλέα έχεις δίκιο ρε…respect!

Achilleas: What did I tell you this afternoon? You copied it

Foteini: Achillea you’re right mate...respect!

Example 1 is from Dimitris’s Facebook wall. It consists of a status update, that is to say a short message, with which Dimitris informs his latest score in a computer game. It can easily be discerned that the terms used in English derive from the computer game environment which Dimitris is commenting on. In the context of the literature related to borrowing and code switching before translanguaging began to be discussed, words such as win and promotion could have been classed as core borrowings (Myers-Scotten 1992), that is to say loans that are taken from a donor language, even though there are appropriate equivalents in the matrix language. In other words, in contrast to cultural borrowings, there is no obvious practical need for a word to be borrowed from another language, although a potential interpretation offered by Myers-Scotton is that of the cultural pressure associated with the use of the borrowed word (2006). It is, however, doubtful that Dimitris felt any cultural pressure when choosing the English words in Example 1; rather, he conveys a message to his contacts about his accomplishment in an environment where English is used; as such, commenting on his experience through use of the same code in which the experience was realised. According to Myers-Scotton (1992, p. 33), single-word elements with a low frequency from another language that are found in a matrix language can be considered to be examples of code-switching as opposed to loans [6]. Moreover, the fact that these words can be said to have been chosen by Dimitris to convey his experience that took place in English suits the definition of translanguaging as a use of various languages, combined to communicate meaning and experience from the perspective of the speaker (Tsokalidou 2015, p. 390) [7].

Furthermore, the use of the word bros in the plural, a short form of the word brothers often used in informal cultural settings in English-speaking countries for close friends and particularly in contemporary songs, demonstrate how Dimitris is aware of contemporary English-speaking popular culture (Androutsopoulos 2004), more than likely acquired from outside the classroom environment. The same word also appears in Example 2, in which Pantelis, a boy, is thanking a friend of his for giving him a fish tank as a present for his birthday. The adverb ever in English can be used after comparisons or for added emphasis (Cambridge Dictionary 2018) and is used in both spoken and written communication. The equivalent in Greek, ποτέ, (lit. ‘never’) is used in the same way (Lexico tis Koinis Neas Ellinikis 1998), although it would need to follow a relative clause, such as, in this case, που μου χάρισαν ποτέ, (lit. ‘which I was ever given’), thus making the sentence more complex than the use of the single English word. Therefore, in addition to Pantelis indexing his knowledge and affiliation with English-speaking popular culture, ease of expression could also be a practical reason for his choosing the English over the Greek equivalent.

Example three also displays the use of two single-unit words of English embedded into the Greek matrix language, κόπυ, ‘copy,’ written in Greek and respect. The conversation revolves around Foteini agreeing with her friend Achilleas that a person’s heart is more important than their appearance. In this sense, the use of the English word copy refers to her agreeing with him. There is no obvious reason why Achilleas did not use the Greek verb αντιγράφω, which means the same as ‘copy’; apart from the possibility that αντιγράφω may have a negatively charged illocutionary force, in that it could be though to convey the negative connotation of cheating, a common use to describe cheating in exams, for instance. On the other hand, copy could be seen as an established loanword from English-speaking IT in that it is often used as part of the pair copy-paste, which in informal spoken Greek has been semantically expanded to denote the use of someone’s idea or the repetition of an action. On the other hand, the use of the word respect is another example of a pupil’s exposure and knowledge of popular culture, since it is used as a way of expressing admiration in lower registers of English. One response elicited from my interview with one of the pupils, Aris, was that “we don’t use [the Greek equivalent]...we just say respect [...]” It could therefore be argued that the cultural meaning of the English word is more appropriate for the communicative purpose than the Greek equivalent.

Example 4, on the other hand, written by Dimitris to ask his friends which characters they are in a game, is an interesting instance of how pupils make use of words from English and adapt them to the morphological system of Greek.

4. plz paidia valte ti eiste plzaroo

Plz say what you are guys plzaroo

In this example, the English word please, abbreviated here as plz has been used instead of the Greek equivalent παρακαλώ. However, in addition to being embedded or inserted into the Greek syntactic structure, as is the case in the first instance, the second instance shows the morphological assimilation of the word into Greek by using the morphological verbal suffix –άρω. This particular suffix is commonly attached to verbs from other languages that become assimilated into Greek as established borrowings (Bakakou-Orfanou 2005, p. 156). Examples of this are verbs such as λανσάρω (‘launch’) and παρκάρω (‘park’) (ibid, p. 156), but, more recently perhaps, the verbs γουγκλάρω (‘google’) and τσεκάρω (‘check’). According to Bakakou-Orfanou (ibid) and Poplack et al. (1988), instances such as these as established borrowings, since they show morphological integration. However, as Makri-Tsilipakou (1999b, p. 575) points out, this is not necessarily true in the case of nonce or ad hoc borrowings. Certainly, this would seem to be the case in Example 4, as the verb πλιζάρω (‘pleasaro’) would almost certainly not be considered an element of high frequency in Greek, therefore, according to Myers-Scotton (1992), allowing us to consider it as an example of switching rather than a loanword. Moreover, it reveals the extent to which language users are creative with the resources they possess in both languages, thus conforming to Tsokalidou’s (2016, p. 108) definition of translanguaging as being “a creative linguistic practice that gives expression to new identities that are created in language contact situations[...]”

Finally, in relation to the second trend of larger segments of English that go beyond word level, Examples 5 and 6 are highly indicative, as well as being good examples of creative linguistic practices.

5. Listening in English mpliax

6. Γιάννης: χαχαχαχα!!!

Λία: ουυυυυ *ο* οι ίδιοι!!! ειδικα σε αυτην την φωτοο… σωστα, κ. Παρκερ;

Γιάννης: λαθος!!!

Γιάννης: ουτε το προσωπο του δεν φαινεται

Λία: δολοφονικο βλεμαα…σκααα

Φωτεινή: είστε ίδιοι ρε *ο*

Γιάννης: ΔΕΝ ΕΙΜΑΣΤΕ

Λία: -.- Δεν σου αρέσει ο Spiderman τώρα; Are you working me?

Γιάννης: Νο

Giannis: xaxaxaxa!!!

Lia: ouuuuuu you’re a spitting image!!! Especially in that photo...right, Mr. Parker?

Giannis: Wrong!!!

Giannis: You can’t even see his face

Lia: murderous look...skaaa

Foteini: Spitting image

Giannis: WE’RE NOT

Lia: Don’t you like Spiderman now? Are you working me?

Giannis: No

Example 5, written by Jenny, more than likely refers to her doing a listening exercise in English in preparation for an English language examination. The experience is expressed in the same language. However, Jenny reverts to Greek to express her opinion of the activity she is engaged in by using the interjection μπλιαχ (bliach, ‘eugh’), used to express disgust. This can be seen of an example of translanguaging where experiences are linguistically expressed by using the language through which they take place, in this case an English listening exercise, whereas through use of the Greek interjection, the identity of the writer as a Greek teenager who disapproves of the aforementioned activity is indexed (see Bucholtz & Hall 2005, p. 586). Moreover, code switching is also associated with a change in register (Gumperz 1982). As a result, the change of language seen in Example 5 could be viewed as a shift from statement to personal stance or evaluation.

Finally, Example 6 is an exchange between Giannis and Lia. Lia is trying to convince Giannis that he looks like Mr. Parker, whose alter ego is Spiderman. Giannis resists this claim and Lia responds by asking him by expressing her surprise that he does not like Superman, proceeding to pose the question, are you working me, a word-for-word translation from the Greek με δουλεύεις (lit. ‘are you kidding me’). This switch from Greek to English seems to motivate Giannis to respond in English by using the word no, as opposed to the Greek equivalent, όχι. The renegotiating of the code of communication between participants after an utterance in another language is considered to be code switching par excellence (Makri-Tsilipakou 1999b, p. 577). What is interesting in this particular instance is that the expression in question, being a direct translation from the Greek, would not be intelligible had the comment been directed at a non-Greek speaking participant. This shows what Androutsopoulos (2013a) means by the term networked multilinualism, namely, using language and combinations of languages in a way that reflects the sociolinguistic background of those participating in the network, in this case, on Facebook. In prescriptive terms, it could be considered to be a “violation” of the grammatical rules of language and would almost certainly be viewed as such in education which focuses on teaching the standard form. However, examples such as these fit in with Jørgensen’s (2008) understanding of languaging, namely speakers’ use of the linguistic resources they have to convey meaning, regardless of degree of proficiency and grammatical rules, which he sees as a reality of everyday language use. Lia herself explains to me in her interview that she would not use an expression such as this if she were speaking with and English person who did not know Greek. This also fits in with Tsokalidou’s view of translaguaging as being a creative linguistic practice (2016).

Examples such as 5 and 6 are highly significant for the language classroom as they diverge from the standard norms that we saw in section 2. However, as we have discussed, examples of translanguaging such as these form an integral part of learners’ everyday communication, in which they draw on their knowledge of both Greek and English to communicate experiences and opinions. In the following section, I put forward suggestions as to how such practices can be brought into the EFL classroom in Greece.

5. Proposals for bringing translanguaging into the classroom

From the analysis and discussion so far, two main conclusions can be drawn that are relevant for the language classroom. Firstly, in reverse order, pupils in Greece use and combine the linguistic resources they have in English and Greek to convey meaning and experiences, often in highly creative ways which violate the rules of the standard variety but achieve the desired communicative goal, since they are directed at fellow Greek speakers. Moreover, the examples of translaguaging we saw in section 4 demonstrate how the English linguistic resources the pupils draw from for their online communication transcend the more confined examples of language that is taught them in secondary school EFL classes, since they derive from areas connected with the teenagers’ day to day lives such as playing video games, watching films and doing language-related work such as listening activities.

Secondly, the review of the teaching material used for English in Greek secondary schools demonstrated how, although an attempt has been made to incorporate online communication into the activities, there is a distinct lack of focus on the socio-pragmatic aspects of language use in online settings. On the contrary, activities currently used in EFL textbooks focus on grammatical properties of the standard variety, thus effectively rendering reference to online communication irrelevant to the activities. This situation is a good and current example of what has been termed the Home-School Mismatch Hypothesis (Stamou et al. 2016). Working on the premise of current literature that it is important for language learners to be exposed to a wide range of language varieties and genres (Beiswanger 2008, Tsiplakou & Hadjioannou 2010, Tsiplakou 2016), which include the standard varieties of English, it is not my intention to advocate the replacement of standard varieties in favour of features of online communication and, in particular, translaguaging. Rather, I advocate a more inclusive approach to language teaching that could supplement existing material with activities which include aspects of translanguaging, so as to boost learners’ critical awareness of language use and make the language covered in class more relevant to the lives of teenage learners; in line with current teaching trends (Koutsogiannis 2012). I shall, therefore, outline here two potential supplementary activities that may serve this purpose.

Activity 1 presents data from Examples 1,2 and 3 that we saw in the previous section. Pupils are presented with the data and then asked to carry out some activities based on the examples shown.

Activity 1: Read the three Facebook status updates below and then answer the questions that follow.

BROS [...] KAI [...] 1 WIN AKOMA KAI KSANAPAO PROMOTIONTo kalitero dwro ever! Thanx bro

Αχιλλέας: Τι σου ειπα εγω το μεσημέρι? Κοπυ το εκανες

Φωτεινή: Αχιλλέα έχεις δίκιο ρε…respect!Question 1: What do you think the three status updates are referring to?

Question 2: Can you find any uses of English in the three examples?

Question 3: Can you find the Greek words for the examples in English?

Question 4: Why do you think the owner’s of the Facebook profiles have used English in the examples?

Question 5: Discuss your answer to Question 4 with the rest of the class.

The purpose of Activity 1 is to elicit the pupils’ interpretation of why English has been used in the examples above. Questions 1 and 4 have been structured as open-ended questions (Dimitropoulos 2001), so as to allow the pupils to develop their own assessment of the context and reasons that motivated the users of Facebook to use English. In short, Question 1 asks pupils to read through the updates to familiarise themselves with the context and to try and establish who the participants are and what they are referring to, questions 2 and 3 asks them to find examples of English and their Greek equivalents, and question 4 asks them to explain in their own words why they believe the users have chosen English, as opposed to Greek, to convey these particular messages. It is hoped that open-ended questions such as these will allow the pupils to critically engage with the language and formulate their own ideas as opposed to being led to a response by the book or teacher. Finally, Question 5 asks them to present their responses to the rest of the class and discuss their opinions, allowing pupils to critically analyse their ideas and exchange their points of view with each other, an approach that has been shown to be a useful component of interpreting language from the perspective of critical language awareness (Karagiannaki & Stamou 2018).

Activity 2 has been taken from Example 6 in the previous section. For this activity in Questions 1 and 2, pupils are once again asked to formulate an opinion regarding the context in which the online conversation takes place, namely the topic of discussion, the participants and their intentions. Subsequently, in Question 3 they are asked to comment on the example of translanguaging used, to discuss the communicative instances in which it would be appropriate to use it and, to find an alternative way of writing it in English in Question 4 and, finally in Question 5, to think of similar examples from their own experience on social media to present to the class.

Activity 2: Read the following discussion from Facebook and answer the questions that follow.

Γιάννης: χαχαχαχα!!!

Λία: ουυυυυ *ο* οι ίδιοι!!! ειδικα σε αυτην την φωτοο… σωστα, κ. Παρκερ;

Γιάννης: λαθος!!!

Γιάννης: ουτε το προσωπο του δεν φαινεται

Λία: δολοφονικο βλεμαα…σκααα

Φωτεινή: είστε ίδιοι ρε *ο*

Γιάννης: ΔΕΝ ΕΙΜΑΣΤΕ

Λία: -.- Δεν σου αρέσει ο Spiderman τώρα; Are you working me?

Γιάννης: ΝοQuestion 1: In your opinion, who is involved in the discussion? Explain your answers.

Question 2: What do you think the two people are talking about?

Question 3: Look at the English phrase that is used by Lia. What does it mean and when and with whom would you use this particular phrase?

Question 4: Can you think of another way of writing the phrase in English?

Question 5: Can you find other similar examples of English on social media? Bring them into class next time and discuss.

The advantage of the activities shown here is that they both relate to the pupils’ everyday language practices (Koutsogiannis 2011, 2012) by using authentic material from online posts and conversations of users the same age as the pupils themselves. It is believed that this will contribute to a more inclusive approach to language learning that will highlight and discuss non-standard forms of which are nevertheless used in day-to-day communication. Consequently, pupils engage with and critically analyse language from contemporary and varied forms of literacy, which is in line with current thinking related to language learning today (Street 1993, Cope & Kalantzis 2000, Gee 2004). Facebook, from which the data presented here derive, is a good example of this, but the same logic can be extended to other platforms of Computer-Mediated-Communication, such as Instagram and You Tube, which also form an integral part of young people’s everyday language practices.

6. Conclusions and further steps

This paper aimed to highlight the need for current teaching material to be adapted, so as to include new forms of literacy and language variety that are of relevance to pupils of secondary school age. More specifically, I demonstrated that, while current EFL material used in Greek secondary schools make an effort to refer to online communication as opposed to more traditional modes, the activities mainly focus on formal aspects of standard grammar and not the communicative socio-pragmatic aspects of different varieties of language. In fact, only a couple of examples encourage learners to engage with the material and analyse it from a critical perspective, while examples of multilingual and translanguaging practices were extremely few, thus reinforcing the perception of a “wholesale” view of language, as opposed to the reality of online communication where users employ a wide range of linguistic resources to convey meaning. Moreover, in line with current thinking expressed in the literature, it was argued that including examples of language variety, especially from online communication which makes up a significant part of young people’s language, practices, is an important factor in increasing learners’ awareness of the fact that language is not a uniform entity, but varies according to settings, participants and purpose. Looking at examples of translanguaging in particular highlights the ways in which the boundaries between languages, as opposed to being rigid show a great extent deal of fluidity, where features and structures from various languages may be combined and even violated in order to convey meaning, index identity and play with language.

Working on the premises outlined above, examples of online translanguaging from my own research were discussed. We saw how users borrow from a wide range of linguistic resources to convey meaning with their online contacts. Most strikingly, the English used by the participants in my research demonstrated instances of language contact, in this case Greek and English, which transcend the boundaries of school education and derive from young people’s out-of-school activities, such as playing video games, watching films, listening to music and generally engaging with English-speaking pop culture. In light of this and by using examples from the aforementioned data, two activities were put forward which encourage pupils to determine the context of authentic online communication and critically engage with the content by interpreting it and discussing it with the rest of the class. Opportunities are also given for pupils to find similar examples from their own communication on social media, thus helping to close the gap between out-of-school and school language practices.

The next step in this direction will be to pilot the material in a classroom situation and to measure the extent to which it was successful in engaging learners and helping them develop their critical awareness of language variety. However, three practical issues must be taken into consideration before any definitive conclusions are drawn. Firstly, the extent to which current education authorities at both higher and lower levels will be willing to make the transition from an approach that favours a focus on formal standard forms to a more inclusive variation-oriented approach must be considered. Such a transition differs considerably from approaches currently used in schools and it is not improbable for any suggestions to be met with resistance. Secondly, the extent to which a learner’s critical awareness can be measured or if it is even desirable for it to be measured should be taken into consideration. Recent research suggests ways in which this is possible (Maroniti 2016, Karagiannaki & Stamou 2018), but a clear framework will need to be developed if any sound arguments are to be made in favour of including such examples of language variety in EFL material. Finally, if language variety such as the examples highlighted in this paper are to be included in EFL material used in Greek secondary schools, current material will have to be reviewed significantly, so as to make the transition from a more prescriptive discourse of language to a, as Koutsogiannis (2012, p. 218) puts it, “holistic” discourse, which looks at everyday uses of language. This, of course, should not be taken to mean the replacement of standard forms of English with translanguaing practices, but a more realistic discussion of what really happens “on the ground” regarding language use. This, of course, is no easy task, as elements of older approaches are often mixed with newer ones in contemporary teaching practices (Koutsogiannis: ibid). Consequently, the proposals put forward here should be seen as a contribution to the broader question of how we want to teach language in the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

Some of the research from Facebook discussed in this paper was carried out as part of a Thalis (2011–2015) research project coordinated by Dr. Anastasia G. Stamou, entitled: ‘Linguistic variation and language ideologies in mass cultural texts: Design, development and assessment of learning material for critical language awareness’ (Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, Funding ID: MIS 375599). Other data forms part of my doctoral research for which I am indebted to the Greek Scholarship Foundation (IKY) for funding my PhD research. I would also like to thank the pupils and teachers of the two participating experimental schools of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Macedonia, without whom my research on Facebook would not have been possible. Finally, I would like to thank Professor Dimitris Koutsogiannis for his support and encouragement, and for his invaluable comments on matters of language and education.

Notes

[1] It is important to mention that the philosophy of the studies mentioned is common to both L1 and L2 teaching (Koutsogiannis 2011: 43). However, the development of specific frameworks in both scientific fields which would allow the application of this philosophy remains ongoing.

[2] See Koutsogiannis (2009, 2011, 2012) for a critique of current approaches to bringing children’s out-of-school languages practices into the classroom. In short, although Koutsogiannis recognises the need for current language teaching to embrace new literacies and children’s everyday out-of-school language practices (Koutsogiannis 2011: 46 & 2012: 215), he calls for greater attention to be paid to the historical and socio-political factors that contribute to how these new literacies are approached, from both a global and local perspective.

[3] See Boklund-Lagopoulou (2003) for a convincing explanation of the ideological reasons behind why it is these politically dominant languages in particular that are promoted in Greek state education.

[4] Greeklish refers to users’ use of the Latin alphabet as opposed to the Greek when writing Greek online. The issue was highly controversial at the beginning of the 21st Century among fears that it could be detrimental to the Greek language. See, among others, Koutsogiannis & Mitsikopoulou (2007), Tseliga (2007), Androutsopoulos (2009), Spilioti (2014) and Lees et al (2017) for further discussion on the issue.

[5] The term experimental school refers to schools affiliated with universities and research centres which participate in and apply research carried out at university.

[6] I endorse the theoretical framework put forward by Myers-Scotton, as, rather than seeing established loans, core borrowing and code switching as mutually exclusive, she views them as part of a continuum, on which single word units can both be core borrowings or examples of code switching. Such an approach fits in well with the more modern theory of translanguaging, as it is able to account for ad hoc word choices made by speakers to refer to their experiences and index aspects of their identity. It also allows for the necessary flexibility in categorising the use of foreign language elements, the lack of which has been criticised in other grammar-oriented models (see Sankoff & Poplack 1981).

[7] The distinction between established borrowing, nonce borrowing, and switching has been subject to various criteria and critical points of view, the analysis of which goes beyond the scope and the purpose of this paper. Words in examples such as 1 are analysed here as aspects of translanguaging, as they convey meaning and experience from the perspective of the user and are not considered to be frequently used words in Greek. However, see Poplack (1980), Myers-Scotton (1992), Auer (1999), as well as Bakakou-Orfanou (2005) for a more detailed theoretical discussion.

Références bibliographiques

Androutsopoulos, J. (2004) Non-native English and sub-cultural identities in media discourse. In H. Sandoy, E. Brunstad, J. Hagen & K. Tenfjord (eds.) Den fleirspraklege utfordringa. Oslo: Novus Forlag. 83-98.

Androutsopoulos, J. (2009). Greeklish: Transliteration practice and discourse in a setting of computer-mediated digraphia. In A. Georgakopoulou & M. Silk (eds.) Standard languages and language standards: Greek past and present. Farnam: Ashgate. 221-249.

Androutsopoulos, J. (2013a) Networked multilingualism: Some language practices on Facebook and their implications. International Journal of Bilingualism (19/2). 185-205.

Androutsopoulos, J. (2013b) Online data collection. In C. Mallinson, B. Childs & G.V. Herk (eds.) Data Collection in Sociolinguistics: Methods and Applications. London: Routledge. 236-249.

Androutsopoulos, J. (2014) Computer-mediated Communication and Linguistic Landscapes. In J. Holmes & K. Hazen (eds.) Research Methods in Sociolinguistics: A Practical Guide. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. 74-90.

Auer, P. (1999). From codeswitching via language mixing to fused lects toward a dynamic typology of bilingual speech. International Journal of Bilingualism. (3/4). 309-332.

Bakakou-Orfanou, Α. (2005). I lexi tis Neoellinikis sto glossiko sistima kai sto keimeno [The Modern Greek Word in the Linguistic System and Text]. Athens: Parousia, no. 65.

Bella, S. (2011) I defteri glossa. Kataktisi kai didaskalia. [Second Language: Acquisition and Teaching]. Athens: Politeia.

Bella, S. (2012). Pragmatic awareness in a second language setting: The case of L2 learners of Greek. Multilingua (31). 1-33.

Beiswanger, Μ. (2008). Varieties of English in current English language teaching. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics. Vol. 38. 27-47.

Boklund-Lagopoulou, K. (2003). Teaching English in Greece: An Update. In V. Bolla-Mavrides (ed.) New Englishes. Thessaloniki: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. 11-24.

Bucholtz, Μ. & Hall, Κ. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies. Issue 7 (4/5). 585-614.

Bulfin, S. & Koutsogiannis, D. (2012). New literacies as multiply placed practices: Expanding perspectives on young people’s literacies across home and school. Language & Education (26/4). 331-346.

Cambridge Dictionary (2018) [online]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/ [accessed 14th November 2018].

Coates, J. (1997). Women’s friendships, women’s talk. In R. Wodak (ed.) Gender and Discourse. CA: Sage Publications. 245-263.

Coates, J. (1999) Changing femininities: the talk of teenage girls. In M. Bucholtz, A.C. Liang, L. Sutton (eds.) Reinventing Identities: The Gendered Self in Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 123-144.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2000) (eds.). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

D’Arcy, Α. & Young, Τ.Μ. (2012). Ethics and social media: Implications for sociolinguistics in the networked public. Journal of Sociolinguistics (16/4), 2012. 532-546.

Davydova, J., Maier, G., Siemund, P. (2013). Varieties of English in the EFL classroom setting. In K. Bührig & B. Meyer (eds.). Transferring Linguistic Know-how into Institutional Practice. Hamburg Studies on Multilingualism 15. John Benjamins. 81-94.

Dimitropoulos, E. (2001). Ekpaideftiki axiologisi. I axiologisi tou mathiti. Theoria-praxi-problimata [Education assessment. Pupil assessment. Theory-practice-problems]. Athens: Grigoris.

Galantomos, I. (2012). Mathimata Diglossias [Lessons in Bilingualism]. Athens: Epikentro.

Garcia, O. (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gee, J.P.(2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. London: Routledge.

Giannakopoulou, E, Giannakopoulou, G., Karampasi, E. & Theoni, S. (2009). Think Teen! 2nd Grade of Junior High School. Students’ book. Prochorimenoi. Athens: Organismos Ekdoseos Didaktikon Vivlion.

Gumperz, J.J.(1982). Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jørgensen, N. (2008). Polylingual languaging around and among children and adolescents. International Journal of Multilingualism 5 (3). 161-176.

Hymes, D. (1962). The Ethnography of Speaking. In T. Gladwin & W. C. Sturtevant (eds.), Anthropology and Human Behavior. Washington, DC: Anthropology Society of Washington. 13-53.

Illés, Ε. & Akcan, S. (2017). Bringing real-life language use into EFL classrooms. ELT Journal (17/1). Oxford University Press. 3-12.

Karagiannaki, E. & Stamou, A. (2018). Bringing critical discourse analysis into the classroom: a critical language awareness project on fairy tales for young school children, Language Awareness. Language Awareness. 1-21.

Karagianni, E., Koui, V. & Nikolaki, A. (2009a). Think Teen! First Grade of Junior High School Students‘ Book. Archarioi. Athens: Organismos Ekdoseos Didaktikon Vivlion.

Karagianni, E., Koui, V. & Nikolaki, A. (2009b). Think Teen! First Grade of Junior High School Workbook. Archarioi. Athens: Organismos Ekdoseos Didaktikon Vivlion.

Karagianni, E., Koui, V. & Nikolaki, A. (2009c). Think Teen! First Grade of Junior High School Students‘ Book. Prochorimenoi. Athens: Organismos Ekdoseos Didaktikon Vivlion.

Katsarou, E., Magana, A., Skia, A., Tseliou, B. (2012). Neoelliniki Glossa G’ Gymnasiou [Modern Greek Language: Third Class of High School]. Athens: Organismos Ekdoseos Didaktikon Vivlion.

Koutsogiannis, D. (2009). Discourses in researching children’s digital literacy practices: Reviewing the “home/school mismatch hypothesis” in the globalisation era. In D. Koutsogiannis & M. Arapopoulou (eds.). Literacy, New Technologies and Education: Aspects of the Local and Global. Thessaloniki: Zitis. 207-230.

Koutsogiannis, D. (2011). ICTs and language teaching: The missing third circle. In G. Stickel, & T. Váradi (eds.). Language, Languages and New Technologies: ICT in the Service of Languages. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag. 43-59.

Koutsogiannis, D. (2012). O romvos tis glossikis ekpaidevsis. Meletes gia tin elliniki glossa. 32. Thessaloniki: Institouto Neoellinikon Spoudon. 208-222.

Koutsogiannis, D. & Mitsikopoulou, B. (2007). Greeklish and Greekness: Trends and discourses of “Glocalness.” In Β. Danet, B. & S.C. Herring (eds.), The Multilingual Internet: Language, Culture and Communication Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 143-160.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage.

Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lees, C. (2017). Glossikes praktikes ton neon se topous koinonikis diktiosis: H periptosi tou Facebook [The language practices of young people on social networking sites: the case of Facebook]. PhD thesis. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Lees, C., Politis, P. and Koutsogiannis, D. (2017). Roman-alphabeted Greek and transliteration in the digital language practices of Greek secondary school pupils on Facebook. Journal of Greek Media & Culture (3/1). 53–71.

Lexiko tis Koinis Neoellinikis (1998). Thessaloniki: Institouto Neoellinikon Spoudon. Available at:

http://www.greek-language.gr/greekLang/modern_greek/tools/lexica/triantafyllides/ [accessed 14th November 2018].

Lightbown, P. & N. Spada (2006). How Languages are Learned. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Makri-Tsilipakou, Μ. (1999a). Q: Do you use foreign words when you speak? [In Greek] A: Never! (Laughter). In A.F. Christidis (ed.) Strong and weak languages in the European Union: Aspects of linguistic hegemonism. Vol. 1. Thessaloniki: Centre for the Greek Language. 448-457.

Makri-Tsilipakou, M. (1999b). Neoelliniki kai xenoglosses monades: Daneismos i allagi kodika? [Modern Greek and foreign language units: Borrowing or Code Switching?]. In A. Moser (ed.) Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on the Greek Language. Athens: Elliniki Grammata. 575-585.

Maroniti, K. (2016). Anaparastaseis tis glossikis poikilotitas ston tileoptiko logo: Efarmozontas ena programma kritikou grammatismou se paidia protoscholikis ilikias [Representations of language variety in TV discourse: The application of a Critical Literacy syllabus for pre-school children]. In Stamou. A., Politis, P. & Archakis, A. (2016) (eds.). Glossiki poikilotita kai kritikoi grammatismoi ston logo tis mazikis koultouras: Ekpaideftikes protaseis gia to glossiko mathima. Kavala: Saita Publications. 57-94

Mesthrie, R., Swann, J., Deumert, A., Leap, W.L.(2000). Introducing Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1992). Comparing codeswitching and borrowing. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. (13/1-2): 19-39.

Myers-Scotton, C. (2006). Multiple voices: An introduction to bilingualism. Carlton, Australia: Blackwell Publishing.

Poplack, S. (1980). Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en español. Linguistics 18: 581-618.

Poplack, S., Sankoff, D. & Miller, C. (1988). The social correlates and linguistic processes of lexical borrowing and assimilation. Linguistics 26. 47-104.

Sankoff, D., & Poplack, S. (1981). A formal grammar for code-switching. Papers in Linguistics: International Journal of Human Communication (14/1). 3-45.

Sharma, B. (2012) Beyond social networking: performing global Englishes in Facebook by college youth in Nepal. Journal of Sociolinguistics (16/4). 483-509.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (1999). Glossiki fthora, glossikos thanatos, glossiki dolofonia: Diaforetika gegonota h diaforetikes ideologies? [Language decay, language death, language murder: Different events or different ideologies?]. In In A.F. Christidis (ed.) Strong and weak languages in the European Union: Aspects of linguistic hegemonism. Vol. 1. Thessaloniki: Centre for the Greek Language. 74-90.

Stamou. A., Politis, P. & Archakis, A. (2016) (eds.). Glossiki poikilotita kai kritikoi grammatismoi ston logo tis mazikis koultouras: Ekpaideftikes protaseis gia to glossiko mathima [Language variation and critical literacy in popular culture discourse: Teaching proposals for language classes]. Kavala: Saita Publications.

Street, B.V.(1993). The New Literacy Studies: Guest editorial. Journal of Research in Reading (16/2): 81-97.

Spilioti, T. (2014). Greek-Alphabet English: Vernacular transliterations of English in social media. Proceedings of the 46th Annual Meeting of the British Association for Applied Linguistics, Edinburgh 5-7 September 2013. Edinburgh: Heriot-Watt University. 435-447.

Thomason, S.G.(2001). Language Contact: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Tseliga, Τ. (2007). “It’s all Greeklish to Me!” Linguistic and sociocultural perspectives on Roman-Alphabeted Greek in asynchronous computer-Mediated communication. In B. Danet & S.C. Herring (eds.), The Multilingual Internet: Language, Culture and Communication Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 117-141.

Tsiplakou, S. & Chatzioannou, Χ. (2010). I didaskalia tis glossikis poikilotitas: Mia didaktiki paremvasi [Teaching linguistic variation: a teaching intervention]. Meletes gia tin elliniki glossa 30. 617-629.

Tsiplakou, S. (2016) «Ακίνδυνη» εναλλαγή κωδίκων και διαγλωσσικότητα: It’s complicated. Επιστήμες της Αγωγής. Θεματικό Τεύχος 2015, 140-160.

Tsiplakou, S., E. Ioannidou & X. Hadjioannou (2018) Capitalizing on language variation in Greek Cypriot education. Linguistics and Education 45, 62-71.

Tsokalidou, P. (2006). Enallagi kodikon kai fylo: I Ellinoavstraliani periptosi [Code Switching and gender: I Greek-Australian case]. In Th.-S. Pavlidou (ed.) Gloss-Genos-Fylo. 2nd edition. Thessaloniki: Institouto Neoellinikon Spoudon. 203-214.

Tsokalidou, R. (2015). Diglossia kai ekpaidevsi: Apo ti theoria stin praxi kai stin koinoniki drasi [Bilingualism and education: From theory to practice and social action]. In G. Androulakis (ed.). Glossiki Paideia. 35 Meletes Afieromenes ston Kathigiti Napoleonta Mitsi. Athens: Gutenberg. 387-398.

Tsokalidou, R. (2016). Beyond language borders to translanguaging within and outside the educational context. In C.E. Wilson (ed.) Bilingualism: Cultural Influences, Global Perspectives and Advantages/Disadvantages. Nova Science Publishers. 108-118.

Tsokalidou, R. (2017). Sidayes: Beyond Bilingualism to Translanguaging. Athens: Gutenberg.

Tsokalidou, R. & Koutoulis, K. (2015). I diaglossikotita sto elliniko ekpaideftiko sistima: Mia proti dierevnisi [Translanguaging in the Greek education system: An initial investigation]. In A. Chatzidaki (ed.) Koinonioglossologikes kai diapolitismikes proseggiseis stin politismiki eterotita sto scholeio. Epistimes agogis. Issue 2015. Rethimno: University of Crete. 161-181.

Weber, R. P.(1990). Basic Content Analysis. 2nd edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.